Maybe this should be filed under topics that are so obvious that it is not worth writing about. But, I hate to let a good simulation just sit on my computer. I was recently working on a paper investigating the relationship of emotion knowledge (EK) in very young kids with academic performance a year or two later. The idea is that kids who are more emotionally intelligent might be better prepared to learn. My collaborator suspected that the relationship between EK and academics would be different for immigrant and non-immigrant children, so we agreed that this would be a key focus of the analysis.

In model terms, we would describe the relationship for each student as;

where is the academic outcome, is an indicator for immigrant status (either 0 or 1), and is a continuous measure of emotion knowledge. By including the interaction term, we allow for the possibility that the effect of emotion knowledge will be different for immigrants. In particular, if we code for non-immigrant kids and for immigrant kids, represents the relationship of EK and academic performance for non-immigrant kids, and is the relationship for immigrant kids. In this case, non-immigrant kids are the reference category.

Here’s the data generation:

library(simstudy)

library(broom)

set.seed(87265145)

def <- defData(varname = "I", formula = .4, dist = "binary")

def <- defData(def, varname = "EK", formula = "0 + 0.5*I", variance = 4)

def <- defData(def, varname = "T",

formula = "10 + 2*I + 0.5*EK + 1.5*I*EK", variance = 4 )

dT <- genData(250, def)

genFactor(dT, "I", labels = c("not Imm", "Imm"))## id I EK T fI

## 1: 1 1 -1.9655562 5.481254 Imm

## 2: 2 1 0.9230118 16.140710 Imm

## 3: 3 0 -2.5315312 9.443148 not Imm

## 4: 4 1 0.9103722 15.691873 Imm

## 5: 5 0 -0.2126550 9.524948 not Imm

## ---

## 246: 246 0 -1.2727195 7.546245 not Imm

## 247: 247 0 -1.2025184 6.658869 not Imm

## 248: 248 0 -1.7555451 11.027569 not Imm

## 249: 249 0 2.2967681 10.439577 not Imm

## 250: 250 1 -0.3056299 11.673933 ImmLet’s say our primary interest in this exploration is point estimates of and , along with 95% confidence intervals of the estimates. (We could have just as easily reported , but we decided the point estimates would be more intuitive to understand.) The point estimates are quite straightforward: we can estimate them directly from the estimates of and . And the standard error (and confidence interval) for can be read directly off of the model output table. But what about the standard error for the relationship of EK and academic performance for the immigrant kids? How do we handle that?

I’ve always done this the cumbersome way, using this definition:

In R, this is relatively easy (though maybe not super convenient) to do manually, by extracting the information from the estimated parameter variance-covariance matrix.

First, fit a linear model with an interaction term:

lm1 <- lm(T ~ fI*EK, data = dT)

tidy(lm1)## term estimate std.error statistic p.value

## 1 (Intercept) 10.161842 0.16205385 62.706574 2.651774e-153

## 2 fIImm 1.616929 0.26419189 6.120281 3.661090e-09

## 3 EK 0.461628 0.09252734 4.989098 1.147653e-06

## 4 fIImm:EK 1.603680 0.13960763 11.487049 9.808529e-25The estimate for the relationship of EK and academic performance for non-immigrant kids is 0.46 (se = 0.093). And the point estimate for the relationship for immigrant kids is

The standard error can be calculated from the variance-covariance matrix that is derived from the linear model:

vcov(lm1)## (Intercept) fIImm EK fIImm:EK

## (Intercept) 0.026261449 -0.026261449 -0.000611899 0.000611899

## fIImm -0.026261449 0.069797354 0.000611899 -0.006838297

## EK -0.000611899 0.000611899 0.008561309 -0.008561309

## fIImm:EK 0.000611899 -0.006838297 -0.008561309 0.019490291

The standard error of the estimate is .

So?

OK - so maybe that isn’t really all that interesting. Why am I even talking about this? Well, in the actual study, we have a fair amount of missing data. In some cases we don’t have an EK measure, and in others we don’t have an outcome measure. And since the missingness is on the order of 15% to 20%, we decided to use multiple imputation. We used the mice package in R to impute the data, and we pooled the model estimates from the completed data sets to get our final estimates. mice is a fantastic package, but one thing that is does not supply is some sort of pooled variance-covariance matrix. Looking for a relatively quick solution, I decided to use bootstrap methods to estimate the confidence intervals.

(“Relatively quick” is itself a relative term, since bootstrapping and imputing together is not exactly a quick process - maybe something to work on. I was also not fitting standard linear models but mixed effect models. Needless to say, it took a bit of computing time to get my estimates.)

Seeking credit (and maybe some sympathy) for all of my hard work, I mentioned this laborious process to my collaborator. She told me that you can easily estimate the group specific effects merely by changing the reference group and refitting the model. I could see right away that the point estimates would be fine, but surely the standard errors would not be estimated correctly? Of course, a few simulations ensued.

First, I just changed the reference group so that would be measuring the relationship of EK and academic performance for immigrant kids, and would represent the relationship for the non-immigrant kids. Here are the levels before the change:

head(dT$fI)## [1] Imm Imm not Imm Imm not Imm not Imm

## Levels: not Imm ImmAnd after:

dT$fI <- relevel(dT$fI, ref="Imm")

head(dT$fI)## [1] Imm Imm not Imm Imm not Imm not Imm

## Levels: Imm not ImmAnd the model:

lm2 <- lm(T ~ fI*EK, data = dT)

tidy(lm2)## term estimate std.error statistic p.value

## 1 (Intercept) 11.778770 0.2086526 56.451588 8.367177e-143

## 2 fInot Imm -1.616929 0.2641919 -6.120281 3.661090e-09

## 3 EK 2.065308 0.1045418 19.755813 1.112574e-52

## 4 fInot Imm:EK -1.603680 0.1396076 -11.487049 9.808529e-25The estimate for this new is 2.07 (se=0.105), pretty much aligned with our estimate that required a little more work. While this is not a proof by any means, I did do variations on this simulation (adding other covariates, changing the strength of association, changing sample size, changing variation, etc.) and both approaches seem to be equivalent. I even created 10000 samples to see if the coverage rates of the 95% confidence intervals were correct. They were. My collaborator was right. And I felt a little embarrassed, because it seems like something I should have known.

But …

Would this still work with missing data? Surely, things would go awry in the pooling process. So, I did one last simulation, generating the same data, but then added missingness. I imputed the missing data, fit the models, and pooled the results (including pooled 95% confidence intervals). And then I looked at the coverage rates.

First I added some missingness into the data

defM <- defMiss(varname = "EK", formula = "0.05 + 0.10*I",

logit.link = FALSE)

defM <- defMiss(defM, varname = "T", formula = "0.05 + 0.05*I",

logit.link = FALSE)

defM## varname formula logit.link baseline monotonic

## 1: EK 0.05 + 0.10*I FALSE FALSE FALSE

## 2: T 0.05 + 0.05*I FALSE FALSE FALSEAnd then I generated 500 data sets, imputed the data, and fit the models. Each iteration, I stored the final model results for both models (in one where the reference is non-immigrant and the the other where the reference group is immigrant).

library(mice)

nonRes <- list()

immRes <- list()

set.seed(3298348)

for (i in 1:500) {

dT <- genData(250, def)

dT <- genFactor(dT, "I", labels = c("non Imm", "Imm"), prefix = "non")

dT$immI <- relevel(dT$nonI, ref = "Imm")

# generate a missing data matrix

missMat <- genMiss(dtName = dT, missDefs = defM, idvars = "id")

# create obseverd data set

dtObs <- genObs(dT, missMat, idvars = "id")

dtObs <- dtObs[, .(I, EK, nonI, immI, T)]

# impute the missing data (create 20 data sets for each iteration)

dtImp <- mice(data = dtObs, method = 'cart', m = 20, printFlag = FALSE)

# non-immgrant is the reference group

estImp <- with(dtImp, lm(T ~ nonI*EK))

lm1 <- summary(pool(estImp), conf.int = TRUE)

dt1 <- as.data.table(lm1)

dt1[, term := rownames(lm1)]

setnames(dt1, c("2.5 %", "97.5 %"), c("conf.low", "conf.high"))

dt1[, iter := i]

nonRes[[i]] <- dt1

# immgrant is the reference group

estImp <- with(dtImp, lm(T ~ immI*EK))

lm2 <- summary(pool(estImp), conf.int = TRUE)

dt2 <- as.data.table(lm2)

dt2[, term := rownames(lm2)]

setnames(dt2, c("2.5 %", "97.5 %"), c("conf.low", "conf.high"))

dt2[, iter := i]

immRes[[i]] <- dt2

}

nonRes <- rbindlist(nonRes)

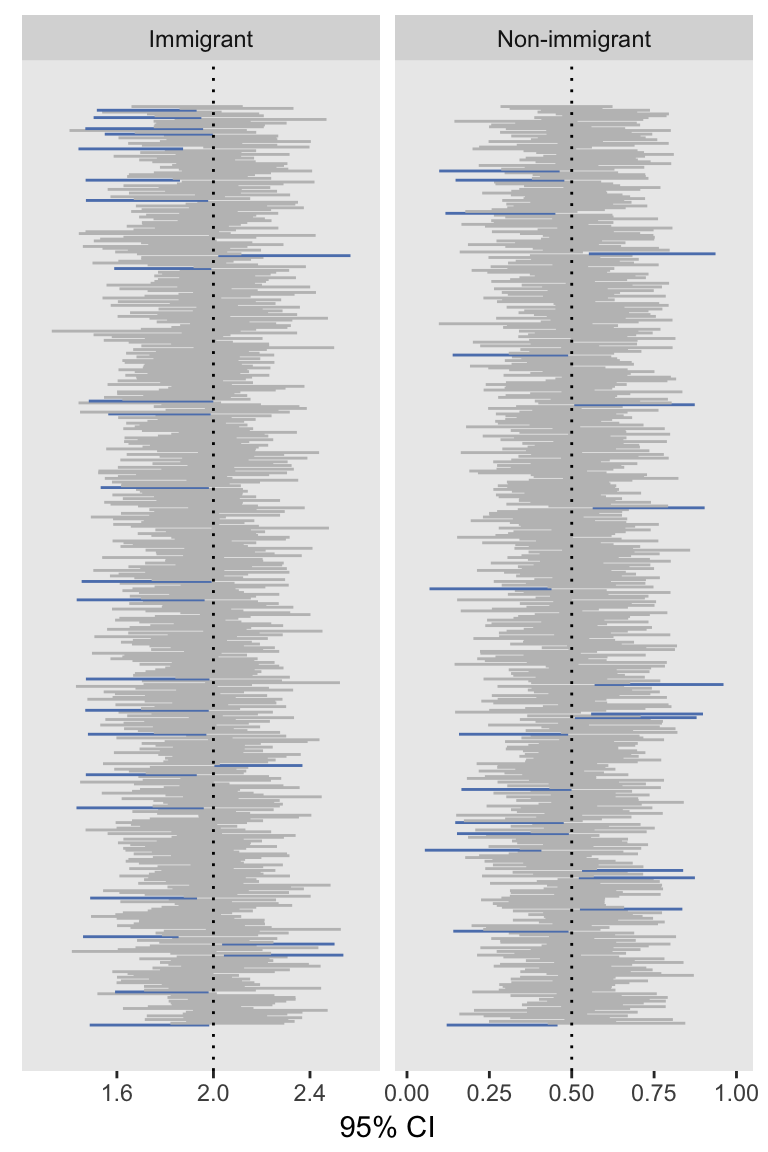

immRes <- rbindlist(immRes)The proportion of confidence intervals that contain the true values is pretty close to 95% for both estimates:

mean(nonRes[term == "EK", conf.low < 0.5 & conf.high > 0.5])## [1] 0.958mean(immRes[term == "EK", conf.low < 2.0 & conf.high > 2.0])## [1] 0.948And the estimates of the mean and standard deviations are also pretty good:

nonRes[term == "EK", .(mean = round(mean(estimate),3),

obs.SD = round(sd(estimate),3),

avgEst.SD = round(sqrt(mean(std.error^2)),3))]## mean obs.SD avgEst.SD

## 1: 0.503 0.086 0.088immRes[term == "EK", .(mean = round(mean(estimate),3),

obs.SD = round(sd(estimate),3),

avgEst.SD = round(sqrt(mean(std.error^2)),3))]## mean obs.SD avgEst.SD

## 1: 1.952 0.117 0.124Because I like to include at least one visual in a post, here is a plot of the 95% confidence intervals, with the CIs not covering the true values colored blue:

The re-reference approach seems to work quite well (in the context of this simulation, at least). My guess is the hours of bootstrapping may have been unnecessary, though I haven’t fully tested all of this out in the context of clustered data. My guess is it will turn out OK in that case as well.

Appendix: ggplot code

nonEK <- nonRes[term == "EK", .(iter, ref = "Non-immigrant",

estimate, conf.low, conf.high,

cover = (conf.low < 0.5 & conf.high > 0.5))]

immEK <- immRes[term == "EK", .(iter, ref = "Immigrant",

estimate, conf.low, conf.high,

cover = (conf.low < 2 & conf.high > 2))]

EK <- rbindlist(list(nonEK, immEK))

vline <- data.table(xint = c(.5, 2),

ref = c("Non-immigrant", "Immigrant"))

ggplot(data = EK, aes(x = conf.low, xend = conf.high, y = iter, yend = iter)) +

geom_segment(aes(color = cover)) +

geom_vline(data=vline, aes(xintercept=xint), lty = 3) +

facet_grid(.~ ref, scales = "free") +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank(),

axis.ticks.y = element_blank(),

axis.text.y = element_blank(),

axis.title.y = element_blank(),

legend.position = "none") +

scale_color_manual(values = c("#5c81ba","grey75")) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(.1, 0), name = "95% CI")