The answer is probably no, because there is a not-so-low chance (perhaps considerably higher than 5%) you will draw the wrong conclusions from the study. I have heard variations on this question not so infrequently, so I thought it would be useful (of course) to do a few quick simulations to see what happens when we try to conduct a study under these conditions. (Another question I get every so often, after a study has failed to find an effect: “can we get a post-hoc estimate of the power?” I was all set to post on the issue, but then I found this, which does a really good job of explaining why this is not a very useful exercise.) But, back to the question at hand.

Here is the bottom line: if there are differences between clusters that relate to the outcome, there is a good chance that we might confuse those inherent differences for treatment effects. These inherent differences could be the characteristics of people in the different clusters; for example, a health care clinic might attract healthier people than others. Or the differences could be characteristics of the clusters themselves; for example, we could imagine that some health care clinics are better at managing high blood pressure than others. In both scenarios, individuals in a particular cluster are likely to have good outcomes regardless of the intervention. And if these clusters happen to get assigned to the intervention, we could easily confuse the underlying structure or characteristics as an intervention effect.

This problem easiest to observe if we generate data with the underlying assumption that there is no treatment effect. Actually, I will generate lots of these data sets, and for each one I am going to test for statistical significance. (I am comfortable doing that in this situation, since I literally can repeat the identical experiment over an over again, a key pre-requisite for properly interpreting a p-value.) I am going to estimate the proportion of cases where the test statistic would lead me to incorrectly reject the null hypothesis, or make a Type I error. (I am not getting into the case where there is actually a treatment effect.)

A single cluster randomized trial with 6 sites

First, I define the cluster level data. Each cluster or site will have a “fixed” effect that will apply to all individuals within that site. I will generate the fixed effect so that on average (across all sites) it is 0 with a variance of 0.053. (I will explain that arbitrary number in a second.) Each site will have exactly 50 individuals.

library(simstudy)

defC <- defData(varname = "siteFix", formula = 0,

variance = .053, dist = "normal", id = "cID")

defC <- defData(defC, varname = "nsite", formula = 50,

dist = "nonrandom")

defC## varname formula variance dist link

## 1: siteFix 0 0.053 normal identity

## 2: nsite 50 0.000 nonrandom identityNow, I generate the cluster-level data and assign treatment:

set.seed(7)

dtC <- genData(6, defC)

dtC <- trtAssign(dtC)

dtCOnce the cluster-level are ready, I can define and generate the individual-level data. Each cluster will have 50 records, for a total of 300 individuals.

defI <- defDataAdd(varname = "y", formula = "siteFix", variance = 1 )

dtI <- genCluster(dtClust = dtC, cLevelVar = "cID", numIndsVar = "nsite",

level1ID = "id")

dtI <- addColumns(defI, dtI)

dtI## cID trtGrp siteFix nsite id y

## 1: 1 0 0.5265638 50 1 2.7165419

## 2: 1 0 0.5265638 50 2 0.8835501

## 3: 1 0 0.5265638 50 3 3.2433156

## 4: 1 0 0.5265638 50 4 2.8080158

## 5: 1 0 0.5265638 50 5 0.8505844

## ---

## 296: 6 1 -0.2180802 50 296 -0.6351033

## 297: 6 1 -0.2180802 50 297 -1.3822554

## 298: 6 1 -0.2180802 50 298 1.5197839

## 299: 6 1 -0.2180802 50 299 -0.4721576

## 300: 6 1 -0.2180802 50 300 -1.1917988I promised a little explanation of why the variance of the sites was specified as 0.053. The statistic that characterizes the extent of clustering is the inter-class coefficient, or ICC. This is calculated by

\[ICC = \frac{\sigma^2_{clust}}{\sigma^2_{clust}+\sigma^2_{ind}}\] where \(\sigma^2_{clust}\) is the variance of the cluster means, and \(\sigma^2_{ind}\) is the variance of the individuals within the clusters. (We are assuming that the within-cluster variance is constant across all clusters.) The denominator represents the total variation across all individuals. The ICC ranges from 0 (no clustering) to 1 (maximal clustering). When \(\sigma^2_{clust} = 0\) then the \(ICC=0\). This means that all variation is due to individual variation. And when \(\sigma^2_{ind}=0\), \(ICC=1\). In this case, there is no variation across individuals within a cluster (i.e. they are all the same with respect to this measure) and any variation across individuals more generally is due entirely to the cluster variation. I used a cluster-level variance of 0.053 so that the ICC is 0.05:

\[ICC = \frac{0.053}{0.053+1.00} \approx 0.05\]

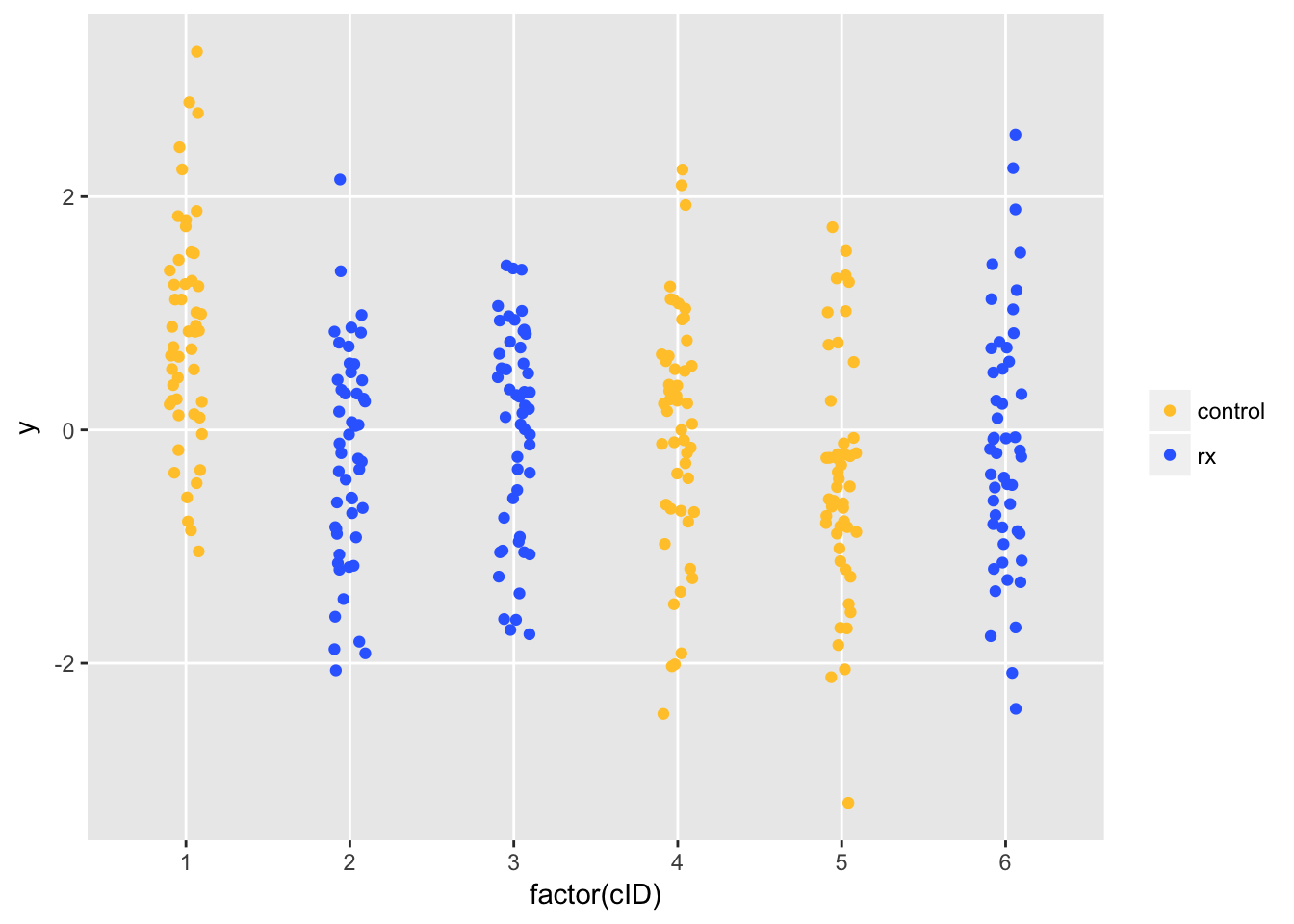

OK - back to the data. Let’s take a quick look at it:

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(data=dtI, aes(x=factor(cID), y=y)) +

geom_jitter(aes(color=factor(trtGrp)), width = .1) +

scale_color_manual(labels=c("control", "rx"),

values = c("#ffc734", "#346cff")) +

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

legend.title = element_blank())

Remember, there is no treatment effect (either positive or negative). But, due to cluster variation, Site 1 (randomized to control) has higher than average outcomes. We estimate the treatment effect using a fixed effects model. This model seems reasonable, since we don’t have enough sites to estimates the variability of a random effects model. We conclude that the treatment has a (deleterious) effect (assuming higher \(y\) is a good thing), based on the p-value for the treatment effect estimate that is considerably less than 0.05.

library(broom)

library(lme4)

lmfit <- lm(y ~ trtGrp + factor(cID), data = dtI)

tidy(lmfit)## term estimate std.error statistic p.value

## 1 (Intercept) 0.8267802 0.1394788 5.9276404 8.597761e-09

## 2 trtGrp -0.9576641 0.1972528 -4.8550088 1.958238e-06

## 3 factor(cID)2 -0.1162042 0.1972528 -0.5891129 5.562379e-01

## 4 factor(cID)3 0.1344241 0.1972528 0.6814812 4.961035e-01

## 5 factor(cID)4 -0.8148341 0.1972528 -4.1309123 4.714672e-05

## 6 factor(cID)5 -1.2684515 0.1972528 -6.4305878 5.132896e-10

A more systematic evaluation

OK, so I was able to pick a seed that generated the outcomes in that single instance that seemed to illustrate my point. But, what happens if we look at this a bit more systematically? The series of plots that follow seem to tell a story. Each one represents a series of simulations, similar to the one above (I am not including the code, because it is a bit convoluted, but would be happy to share if anyone wants it.)

The first scenario shown below is based on six sites using ICCs that range from 0 to 0.10. For each level of ICC, I generated 100 different samples of six sites. For each of those 100 samples, I generated 100 different randomization schemes (which I know is overkill in the case of 6 sites since there are only 20 possible randomization schemes) and generated a new set of individuals. For each of those 100 randomization schemes, I estimated a fixed effects model and recorded the proportion of the 100 where the p-values were below the 0.05 threshold.

How do we interpret this plot? When there is no clustering (\(ICC=0\)), the probability of a Type I error is close to 5%, which is what we would expect based on theory. But, once we have any kind of clustering, things start to go a little haywire. Even when \(ICC=0.025\), we would make a lot of mistakes. The error rate only increases as the extent of clustering increases. There is quite a lot variability in the error rate, which is a function of the variability of the site specific effects.

How do we interpret this plot? When there is no clustering (\(ICC=0\)), the probability of a Type I error is close to 5%, which is what we would expect based on theory. But, once we have any kind of clustering, things start to go a little haywire. Even when \(ICC=0.025\), we would make a lot of mistakes. The error rate only increases as the extent of clustering increases. There is quite a lot variability in the error rate, which is a function of the variability of the site specific effects.

If we use 24 sites, and continue to fit a fixed effect model, we see largely the same thing. Here, we have a much bigger sample size, so a smaller treatment effect is more likely to be statistically significant:

One could make the case that instead of fitting a fixed effects model, we should be using a random effects model (particularly if the sites themselves are randomly pulled from a population of sites, though this is hardly likely to be the case when you are having a hard time recruiting sites to participate in your study). The next plot shows that the error rate goes down for 6 sites, but still not enough for my comfort:

With 24 sites, the random effects model seems much safer to use:

But, in reality, if we only have 6 sites, the best that we could do is randomize within site and use a fixed effect model to draw our conclusions. Even at high levels of clustering, this approach will generally lead us towards a valid conclusion (assuming, of course, the study itself is well designed and implemented):

But, I assume the researcher couldn’t randomize at the individual level, otherwise they wouldn’t have asked that question. In which case I would say, “It might not be the best use of resources.”

But, I assume the researcher couldn’t randomize at the individual level, otherwise they wouldn’t have asked that question. In which case I would say, “It might not be the best use of resources.”