Inspired by a free online course titled Complier Average Causal Effects (CACE) Analysis and taught by Booil Jo and Elizabeth Stuart (through Johns Hopkins University), I’ve decided to explore the topic a little bit. My goal here isn’t to explain CACE analysis in extensive detail (you should definitely go take the course for that), but to describe the problem generally and then (of course) simulate some data. A plot of the simulated data gives a sense of what we are estimating and assuming. And I end by describing two simple methods to estimate the CACE, which we can compare to the truth (since this is a simulation); next time, I will describe a third way.

Non-compliance in randomized trials

Here’s the problem. In a randomized trial, investigators control the randomization process; they determine if an individual is assigned to the treatment group or control group (I am talking about randomized trials here, but many of these issues can apply in the context of observed or quasi-experimental settings, but require more data and assumptions). However, those investigators may not have as much control over the actual treatments that study participants receive. For example, an individual randomized to some type of behavioral intervention may opt not to take advantage of the intervention. Likewise, someone assigned to control may, under some circumstances, figure out a way to get services that are quite similar to the intervention. In all cases, the investigator is able to collect outcome data on all of these patients, regardless of whether or not they followed directions. (This is different from drop-out or loss-to-followup, where outcome data may be missing.)

CACE

Typically, studies analyze data based on treatment assignment rather than treatment received. This focus on assignment is called an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. In a policy environment, the ITT may make a lot of sense; we are answering this specific question: “What is the overall effect in the real world where the intervention is made available yet some people take advantage of it while others do not?” Alternatively, researchers may be interested in different question: “What is the causal effect of actually receiving the treatment?”

Now, to answer the second question, there are numerous subtle issues that you need to wrestle with (again, go take the course). But, long story short, we need to (1) identify the folks in the intervention group who actually do what they have been encouraged to do (receive the intervention) but only because they were encouraged, and not because they would have received the intervention anyways had they not been randomized, and compare their outcomes with (2) the folks in the control group who did not seek out the intervention on their own initiative but would have received the intervention had they been encouraged. These two groups are considered to be compliers - they would always do what they are told in the context of the study. And the effect of the intervention that is based on outcomes from this type of patient is called the complier average causal effect (CACE).

The biggest challenge in estimating the CACE is that we cannot actually identify if people are compliers or not. Some of those receiving the treatment in the intervention group are compliers, but the rest are always-takers. Some of those not receiving the treatment in the control arm are also compliers, but the others are never-takers. There are several methods available to overcome this challenge, two of which I will briefly mention here: method of moments and instrumental variables.

Using potential outcomes to define CACE

In an earlier post, I briefly introduced the idea of potential outcomes. Since we are talking about causal relationships, they are useful here. If is the randomization indicator, for those randomized to the intervention, for those in control. is the indicator of whether or not the individual received the intervention. Since is an outcome, we can imagine the potential outcomes and , or what the value of would be for an individual if or , respectively. And let us say is the outcome, so we have potential outcomes that can be written as and . Think about that for a bit.

Using these potential outcomes, we can define the compliers and the CACE. Compliers are people for whom and . (Never-takers look like this: and . Always-takers: and ). Now, the average causal effect is the average difference between potential outcomes. In this case, the CACE is . The patients for whom and are the compliers.

Simulating data

The data simulation will be based on generating potential outcomes. Observed outcomes will be a function of randomization group and complier status.

options(digits = 3)

library(data.table)

library(simstudy)

library(ggplot2)

# Status :

# 1 = A(lways taker)

# 2 = N(ever taker)

# 3 = C(omplier)

def <- defDataAdd(varname = "Status",

formula = "0.20; 0.40; 0.40", dist = "categorical")

# potential outcomes (PO) for intervention

def <- defDataAdd(def, varname = "M0",

formula = "(Status == 1) * 1", dist = "nonrandom")

def <- defDataAdd(def, varname = "M1",

formula = "(Status != 2) * 1", dist = "nonrandom")

# observed intervention status based on randomization and PO

def <- defDataAdd(def, varname = "m",

formula = "(z==0) * M0 + (z==1) * M1", dist = "nonrandom")

# potential outcome for Y (depends on potential outcome for M)

set.seed(888)

dt <- genData(2000)

dt <- trtAssign(dt, n=2, grpName = "z")

dt <- addColumns(def, dt)

# using data functions here, not simstudy - I need add

# this functionality to simstudy

dt[, AStatus := factor(Status,

labels = c("Always-taker","Never-taker", "Complier"))]

# potential outcomes depend on group status - A, N, or C

dt[Status == 1, Y0 := rnorm(.N, 1.0, sqrt(0.25))]

dt[Status == 2, Y0 := rnorm(.N, 0.0, sqrt(0.36))]

dt[Status == 3, Y0 := rnorm(.N, 0.1, sqrt(0.16))]

dt[Status == 1, Y1 := rnorm(.N, 1.0, sqrt(0.25))]

dt[Status == 2, Y1 := rnorm(.N, 0.0, sqrt(0.36))]

dt[Status == 3, Y1 := rnorm(.N, 0.9, sqrt(0.49))]

# observed outcome function of actual treatment

dt[, y := (m == 0) * Y0 + (m == 1) * Y1]

dt## id z Status M0 M1 m AStatus Y0 Y1 y

## 1: 1 1 3 0 1 1 Complier 0.5088 0.650 0.6500

## 2: 2 1 3 0 1 1 Complier 0.1503 0.729 0.7292

## 3: 3 1 2 0 0 0 Never-taker 1.4277 0.454 1.4277

## 4: 4 0 3 0 1 0 Complier 0.6393 0.998 0.6393

## 5: 5 0 1 1 1 1 Always-taker 0.6506 1.927 1.9267

## ---

## 1996: 1996 0 3 0 1 0 Complier -0.9554 0.114 -0.9554

## 1997: 1997 0 3 0 1 0 Complier 0.0366 0.903 0.0366

## 1998: 1998 1 3 0 1 1 Complier 0.3606 1.098 1.0982

## 1999: 1999 1 3 0 1 1 Complier 0.6651 1.708 1.7082

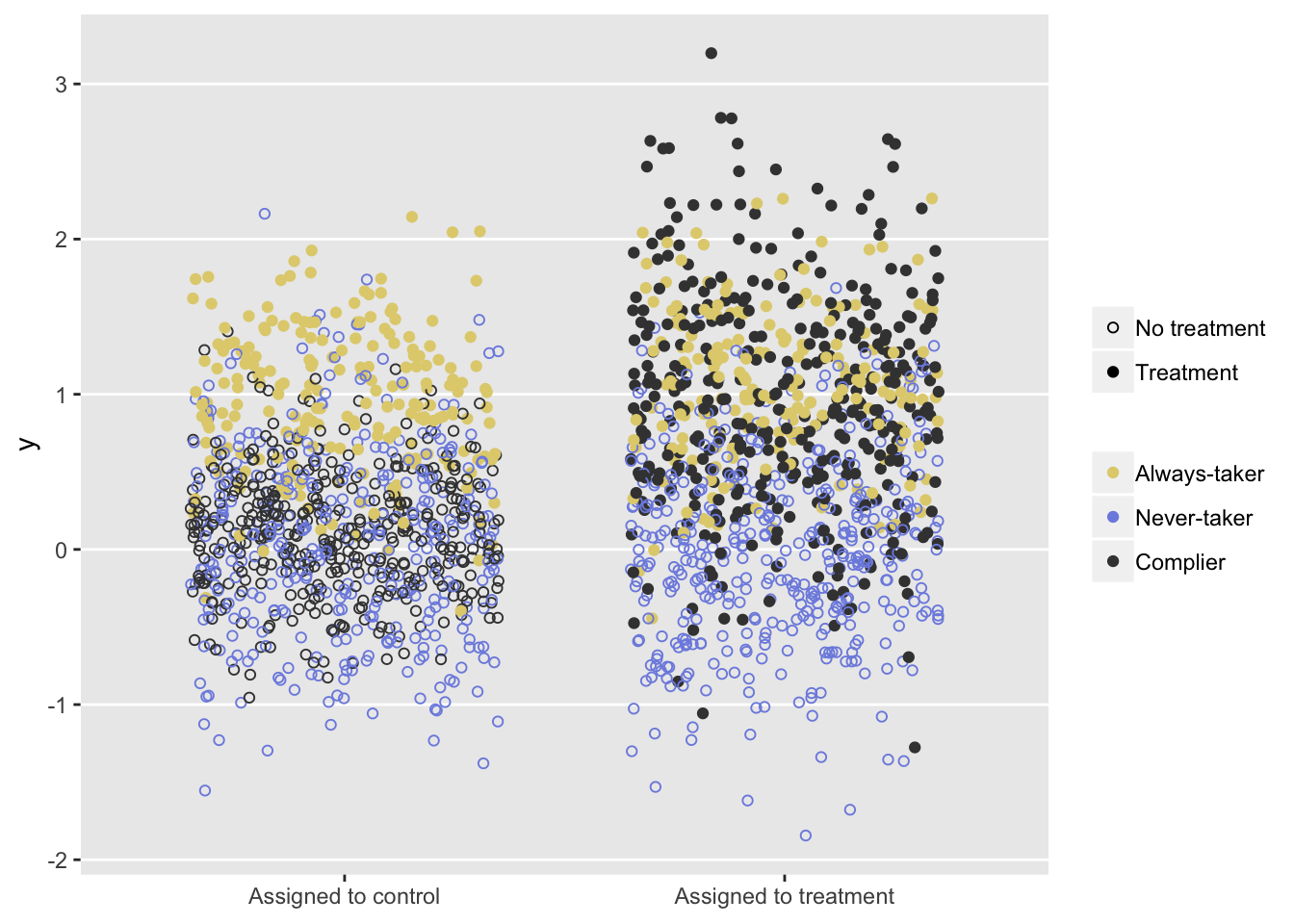

## 2000: 2000 0 3 0 1 0 Complier 0.2207 0.531 0.2207The plot shows outcomes for the two randomization groups. The ITT estimate would be based on an average of all the points in group, regardless of color or shape. The difference between the average of the black circles in the two groups represents the CACE.

ggplot(data=dt, aes(y=y, x = factor(z, labels = c("Assigned to control",

"Assigned to treatment")))) +

geom_jitter(aes(shape=factor(m, labels = c("No treatment", "Treatment")),

color=AStatus),

width = 0.35) +

scale_shape_manual(values = c(1,19)) +

scale_color_manual(values = c("#e1d07d", "#7d8ee1", "grey25")) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = seq(-3, 3, 1), labels = seq(-3, 3, 1)) +

theme(legend.title = element_blank(),

axis.title.x = element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor.y = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major.x = element_blank())

In the real world, we cannot see the colors, yet we need to estimate as if we do, or at least use a method to bypasses that need:

Estimating CACE using observed data

The challenge is to estimate the CACE using observed data only, since that is all we have (along with a couple of key assumptions). We start of by claiming that the average causal effect of treatment assignment () is a weighted average of the three sub-populations of compliers, never-takers, and always-takers:

where is the average causal effect of treatment assignment for the subset of those in the sample who are compliers, is the average causal effect of treatment assignment for the subset who are never-takers, and is the average causal effect for those who are always-takers. , , and represent the sample proportions of compliers, never-takers, and always-takers, respectively.

A key assumption often made to estimate is known as the exclusion restriction: treatment assignment has an effect on the outcome only if it changes the actual treatment taken. (A second key assumption is that there are no deniers, or folks who do the opposite of what they are told. This is called the monotonicity assumption.) This exclusion restriction implies that both and , since in both cases the treatment received is the same regardless of treatment assignment. In that case, we can re-write the equality as

and finally with a little re-arranging,

So, in order estimate , we need to be able to estimate and . Fortunately, we are in a position to do this. Since this is a randomized trial, the average causal effect of treatment assignment is just the difference in observed outcomes for the two treatment assignment groups:

This also happens to be the intention-to-treat ) () estimate.

is a little harder, but in this simplified scenario, not that hard. We just need to follow a little logic: for the control group, we can identify the always-takers (they’re the ones who actually receive the treatment), so we know for the the control group. This can be estimated as . And, since the study was randomized, the distribution of always-takers in the treatment group must be the same. So, we can use estimated from the control group as an estimate for the treatment group.

For the treatment group, we know that . That is everyone who receives treatment in the treatment group is either a complier or always-taker. With this, we can say

But, of course, we argued above that we can estimate as . So, finally, we have

This gives us a method of moments estimator for from observed data:

The simulated estimate

ACE <- dt[z==1, mean(y)] - dt[z==0, mean(y)] # Also ITT

ACE## [1] 0.307pi_C <- dt[z==1, mean(m)] - dt[z==0, mean(m)] # strength of instrument

pi_C## [1] 0.372truth <- dt[AStatus == "Complier", mean(Y1 - Y0)]

truth## [1] 0.81ACE/pi_C## [1] 0.826A method quite commonly used to analyze non-compliance is the instrumental variable model estimated with two-staged least squares regression. The R package ivpack is one of several that facilitates this type of analysis. A discussion of this methodology far exceeds the scope of this post. In any case, we can see that in this simple example, the IV estimate is the same as the method of moments estimator (by looking at the coefficient estimate of m).

library(ivpack)

ivmodel <- ivreg(formula = y ~ m | z, data = dt, x = TRUE)

summary(ivmodel)##

## Call:

## ivreg(formula = y ~ m | z, data = dt, x = TRUE)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.19539 -0.36249 0.00248 0.35859 2.27902

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.0932 0.0302 3.09 0.002 **

## m 0.8262 0.0684 12.08 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.569 on 1998 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-Squared: 0.383, Adjusted R-squared: 0.383

## Wald test: 146 on 1 and 1998 DF, p-value: <2e-16So, again, if I have piqued your interest of this very rich and interesting topic, or if I have totally confused you, go check out the course. In my next post, I will describe a simple latent variable model using a maximum likelihood EM (expectation-maximization) algorithm that arrives at an estimate by predicting complier status.