In my previous post, I described a continuous data generating process that can be used to generate discrete, categorical outcomes. In that post, I focused largely on binary outcomes and simple logistic regression just because things are always easier to follow when there are fewer moving parts. Here, I am going to focus on a situation where we have multiple outcomes, but with a slight twist - these groups of interest can be interpreted in an ordered way. This conceptual latent process can provide another perspective on the models that are typically applied to analyze these types of outcomes.

Categorical outcomes, generally

Certainly, group membership is not necessarily intrinsically ordered. In a general categorical or multinomial outcome, a group does not necessarily have any quantitative relationship vis a vis the other groups. For example, if we were interested in primary type of meat consumption, individuals might be grouped into those favoring (1) chicken, (2) beef, (3) pork, or (4) no meat. We might be interested in estimating the different distributions across the four groups for males and females. However, since there is no natural ranking or ordering of these meat groups (though maybe I am just not creative enough), we are limited to comparing the odds of being in one group relative to another for two exposure groups A and B, such as

.

Ordinal outcomes

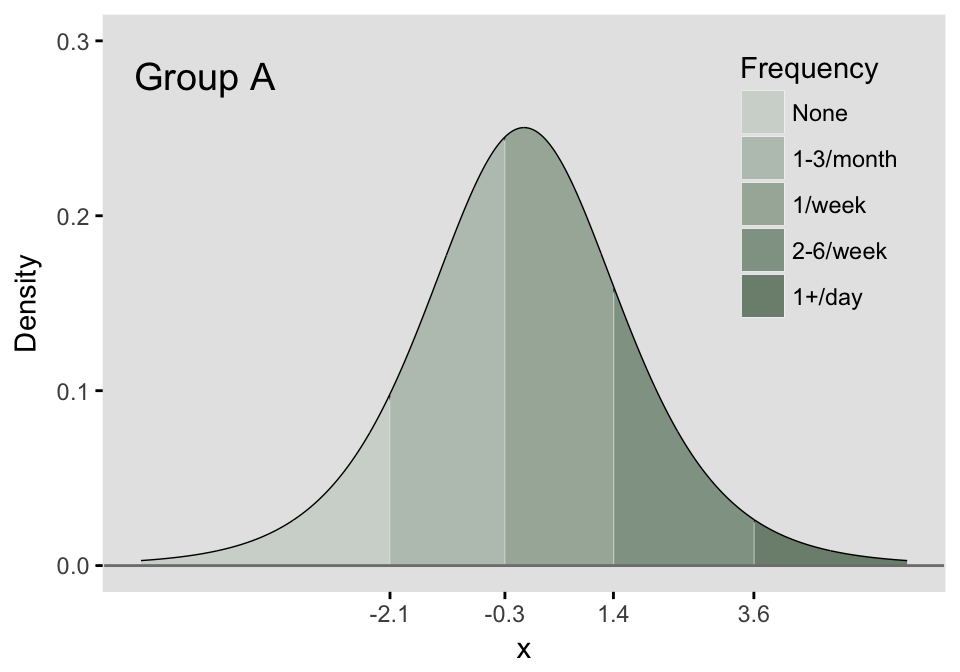

Order becomes relevant when the categories take on meanings related strength of opinion or agreement (as in a Likert-type response) or frequency. In the motivating example I described in the initial post, the response of interest was the frequency meat consumption in a month, so the response categories could be (1) none, (2) 1-3 times per month, (3) once per week, (4) 2-6 times per week, (5) 1 or more times per day. Individuals in group 2 consume meat more frequently than group 1, individuals in group 3 consume meat more frequently than those both groups 1 & 2, and so on. There is a natural quantitative relationship between the groups.

Once we have thrown ordering into the mix, we can expand our possible interpretations of the data. In particular it is quite common to summarize the data by looking at cumulative probabilities, odds, or log-odds. Comparisons of different exposures or individual characteristics typically look at how these cumulative measures vary across the different exposures or characteristics. So, if we were interested in cumulative odds, we would compare

and continue until the last (in this case, fourth) comparison

Multiple responses, multiple thresholds

The latent process that was described for the binary outcome is extended to the multinomial outcome by the addition of more thresholds. These thresholds define the portions of the density that define the probability of each possible response. If there are possible responses (in the meat example, we have 5), then there will be thresholds. The area under the logistic density curve of each of the regions defined by those thresholds (there will be distinct regions) represents the probability of each possible response tied to that region. In the example here, we define five regions of a logistic density by setting the four thresholds. We can say that this underlying continuous distribution represents the probability distribution of categorical responses for a specific population, which we are calling Group A.

# preliminary libraries and plotting defaults

library(ggplot2)

library(data.table)

my_theme <- function() {

theme(panel.background = element_rect(fill = "grey90"),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

axis.ticks = element_line(colour = "black"),

panel.spacing = unit(0.25, "lines"),

plot.title = element_text(size = 12, vjust = 0.5, hjust = 0),

panel.border = element_rect(fill = NA, colour = "gray90"))

}

# create data points density curve

x <- seq(-6, 6, length = 1000)

pdf <- dlogis(x, location = 0, scale = 1)

dt <- data.table(x, pdf)

# set thresholds for Group A

thresholdA <- c(-2.1, -0.3, 1.4, 3.6)

pdf <- dlogis(thresholdA)

grpA <- data.table(threshold = thresholdA, pdf)

aBreaks <- c(-6, grpA$threshold, 6)

# plot density with cutpoints

dt[, grpA := cut(x, breaks = aBreaks, labels = F, include.lowest = TRUE)]

p1 <- ggplot(data = dt, aes(x = x, y = pdf)) +

geom_line() +

geom_area(aes(x = x, y = pdf, group = grpA, fill = factor(grpA))) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "grey50") +

annotate("text", x = -5, y = .28, label = "Group A", size = 5) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("#d0d7d1", "#bbc5bc", "#a6b3a7", "#91a192", "#7c8f7d"),

labels = c("None", "1-3/month", "1/week", "2-6/week", "1+/day"),

name = "Frequency") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = thresholdA) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, 0.3), name = "Density") +

my_theme() +

theme(legend.position = c(.85, .7),

legend.background = element_rect(fill = "grey90"),

legend.key = element_rect(color = "grey90"))

p1

The area for each of the five regions can easily be calculated, where each area represents the probability of each response:

pA= plogis(c(thresholdA, Inf)) - plogis(c(-Inf, thresholdA))

probs <- data.frame(pA)

rownames(probs) <- c("P(Resp = 1)", "P(Resp = 2)",

"P(Resp = 3)", "P(Resp = 4)", "P(Resp = 5)")

probs## pA

## P(Resp = 1) 0.109

## P(Resp = 2) 0.316

## P(Resp = 3) 0.377

## P(Resp = 4) 0.171

## P(Resp = 5) 0.027As I’ve already mentioned, when we characterize a multinomial response, we typically do so in terms of cumulative probabilities. I’ve calculated several quantities below, and we can see that the logs of the cumulative odds for this particular group are indeed the threshold values that we used to define the sub-regions.

# cumulative probabilities defined by the threshold

probA <- data.frame(

cprob = plogis(thresholdA),

codds = plogis(thresholdA)/(1-plogis(thresholdA)),

lcodds = log(plogis(thresholdA)/(1-plogis(thresholdA)))

)

rownames(probA) <- c("P(Grp < 2)", "P(Grp < 3)", "P(Grp < 4)", "P(Grp < 5)")

probA## cprob codds lcodds

## P(Grp < 2) 0.11 0.12 -2.1

## P(Grp < 3) 0.43 0.74 -0.3

## P(Grp < 4) 0.80 4.06 1.4

## P(Grp < 5) 0.97 36.60 3.6The last column of the table below matches the thresholds defined in vector thresholdA.

thresholdA## [1] -2.1 -0.3 1.4 3.6Comparing response distributions of different populations

In the cumulative logit model, the underlying assumption is that the odds ratio of one population relative to another is constant across all the possible responses. This means that all of the cumulative odds ratios are equal:

In terms of the underlying process, this means that each of the thresholds shifts the same amount, as shown below, where we add 1.1 units to each threshold that was set Group A:

# Group B threshold is an additive shift to the right

thresholdB <- thresholdA + 1.1

pdf <- dlogis(thresholdB)

grpB <- data.table(threshold = thresholdB, pdf)

bBreaks <- c(-6, grpB$threshold, 6)Based on this shift, we can see that the probability distribution for Group B is quite different:

pB = plogis(c(thresholdB, Inf)) - plogis(c(-Inf, thresholdB))

probs <- data.frame(pA, pB)

rownames(probs) <- c("P(Resp = 1)", "P(Resp = 2)",

"P(Resp = 3)", "P(Resp = 4)", "P(Resp = 5)")

probs## pA pB

## P(Resp = 1) 0.109 0.269

## P(Resp = 2) 0.316 0.421

## P(Resp = 3) 0.377 0.234

## P(Resp = 4) 0.171 0.067

## P(Resp = 5) 0.027 0.009Plotting Group B along with Group A, we can see visually how that shift affects the sizes of the five regions (I’ve left the thresholds of Group A in the Group B plot so you can see clearly the shift).

# Plot density for group B

dt[, grpB := cut(x, breaks = bBreaks, labels = F, include.lowest = TRUE)]

p2 <- ggplot(data = dt, aes(x = x, y = pdf)) +

geom_line() +

geom_area(aes(x = x, y = pdf, group = grpB, fill = factor(grpB))) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "grey5") +

geom_segment(data=grpA,

aes(x=threshold, xend = threshold, y=0, yend=pdf),

size = 0.3, lty = 2, color = "#857284") +

annotate("text", x = -5, y = .28, label = "Group B", size = 5) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("#d0d7d1", "#bbc5bc", "#a6b3a7", "#91a192", "#7c8f7d"),

labels = c("None", "1-3/month", "1/week", "2-6/week", "1+/day"),

name = "Frequency") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = thresholdB) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0.0, 0.3), name = "Density") +

my_theme() +

theme(legend.position = "none")

library(gridExtra)

grid.arrange(p1, p2, nrow = 2 )

When we look at the cumulative odds ratio comparing the odds of Group B to Group A for each response category, we see a constant ratio. And, of course, a constant log odds ratio, which also reflects the size of the shift from Group A to Group B.

# cumulative probabilities defined by the threshold

probB <- data.frame(

cprob = plogis(thresholdB),

codds = plogis(thresholdB)/(1-plogis(thresholdB)),

lcodds = log(plogis(thresholdB)/(1-plogis(thresholdB)))

)

oddsratio <- data.frame(coddsA = probA$codds,

coddsB = probB$codds,

cOR = probB$codds / probA$codds,

logcOR = log(probB$codds / probA$codds)

)

rownames(oddsratio) <- c("P(Grp < 2)", "P(Grp < 3)", "P(Grp < 4)", "P(Grp < 5)")

oddsratio## coddsA coddsB cOR logcOR

## P(Grp < 2) 0.12 0.37 3 1.1

## P(Grp < 3) 0.74 2.23 3 1.1

## P(Grp < 4) 4.06 12.18 3 1.1

## P(Grp < 5) 36.60 109.95 3 1.1The cumulative proportional odds model

In the R package ordinal, the model is fit using function clm. The model that is being estimated has the form

The model specifies that the cumulative log-odds for a particular category is a function of two parameters, and . (Note that in this parameterization and the model fit, is used.) represents the cumulative log odds of being in category or lower for those in the reference exposure group, which in our example is Group A. also represents the threshold of the latent continuous (logistic) data generating process. is the cumulative log-odds ratio for the category comparing Group B to reference Group A. also represents the shift of the threshold on the latent continuous process for Group B relative to Group A. The proportionality assumption implies that the shift of the threshold for each of the categories is identical. This is what I illustrated above.

Simulation and model fit

To show how this process might actually work, I am simulating data from the standardized logistic distribution and applying the thresholds defined above based on the group status. In practice, each individual could have her own set of thresholds, depending on her characteristics (gender, age, etc.). In this case, group membership is the only characteristic I am using, so all individuals in a particular group share the same set of thresholds. (We could even have random effects, where subgroups have random shifts that are subgroup specific. In the addendum, following the main part of the post, I provide code to generate data from a mixed effects model with group level random effects plus fixed effects for exposure, gender, and a continuous outcome.)

set.seed(123)

n = 1000

x.A <- rlogis(n)

acuts <- c(-Inf, thresholdA, Inf)

catA <- cut(x.A, breaks = acuts, label = F)

dtA <- data.table(id = 1:n, grp = "A", cat = catA)Not surprisingly (since we are using a generous sample size of 1000), the simulated proportions are quite close to the hypothetical proportions established by the thresholds:

cumsum(prop.table(table(catA)))## 1 2 3 4 5

## 0.11 0.44 0.81 0.97 1.00probA$cprob## [1] 0.11 0.43 0.80 0.97Now we generate a sample from Group B and combine them into a single data set:

x.B <- rlogis(n)

bcuts <- c(-Inf, thresholdA + 1.1, Inf)

catB <- cut(x.B, breaks = bcuts, label = F)

dtB <- data.table(id = (n+1):(2*n), grp = "B", cat=catB)

dt <- rbind(dtA, dtB)

dt[, cat := factor(cat, labels = c("None", "1-3/month", "1/week", "2-6/week", "1+/day"))]

dt## id grp cat

## 1: 1 A 1-3/month

## 2: 2 A 1/week

## 3: 3 A 1-3/month

## 4: 4 A 2-6/week

## 5: 5 A 2-6/week

## ---

## 1996: 1996 B 1/week

## 1997: 1997 B 1-3/month

## 1998: 1998 B 1/week

## 1999: 1999 B 1-3/month

## 2000: 2000 B 1-3/monthFinally, we estimate the parameters of the model using function clm and we see that we recover the original parameters quite well.

library(ordinal)

clmFit <- clm(cat ~ grp, data = dt)

summary(clmFit)## formula: cat ~ grp

## data: dt

##

## link threshold nobs logLik AIC niter max.grad cond.H

## logit flexible 2000 -2655.03 5320.05 6(0) 1.19e-11 2.3e+01

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## grpB -1.0745 0.0848 -12.7 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Threshold coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value

## None|1-3/month -2.0912 0.0784 -26.68

## 1-3/month|1/week -0.2465 0.0612 -4.02

## 1/week|2-6/week 1.4212 0.0728 19.51

## 2-6/week|1+/day 3.5150 0.1643 21.39In the model output, the grpB coefficient of -1.07 is the estimate of , which was set to 1.1 in the simulation. The threshold coefficients are the estimates of the ’s in the model, and we can see the estimates are not too bad by looking at the initial thresholds:

coeffit <- coef(clmFit)[1:4]

names(coeffit) <- c(1:4)

rbind( thresholdA, coeffit)## 1 2 3 4

## thresholdA -2.1 -0.30 1.4 3.6

## coeffit -2.1 -0.25 1.4 3.5This was a relatively simple simulation. However it highlights how it would be possible to generate more complex scenarios of multinomial response data to more fully explore other types of models. These more flexible models might be able to handle situations where the possibly restrictive assumptions of this model (particularly the proportional odds assumption) do not hold.

Addendum 1

Here is code to generate cluster-randomized data with an ordinal outcome that is a function of treatment assignment, gender, and a continuous status measure at the individual level. There is also a group level random effect. Once the data are generated, I fit a mixed cumulative logit model.

library(simstudy)

# define data

defSchool <- defData(varname = "reS", formula = 0,

variance = 0.10, id = "idS")

defSchool <- defData(defSchool, varname = "n",

formula = 250, dist = "noZeroPoisson")

defInd <- defDataAdd(varname = "male", formula = 0.45, dist = "binary")

defInd <- defDataAdd(defInd, varname = "status",

formula = 0, variance = 1, dist = "normal")

defInd <- defDataAdd(defInd,

varname = "z",

formula = "0.8 * grp + 0.3 * male - 0.2 * status + reS",

dist = "nonrandom")

# generate data

dtS <- genData(100, defSchool)

dtS <- trtAssign(dtS, grpName = "grp")

dt <- genCluster(dtS, "idS", "n", "id")

dt <- addColumns(defInd, dt)

# set reference probabilities for 4-category outcome

probs <- c(0.35, 0.30, 0.25, 0.10)

cprop <- cumsum(probs)

# map cumulative probs to thresholds for reference group

gamma.c <- qlogis(cprop)

matlp <- matrix(rep(gamma.c, nrow(dt)),

ncol = length(cprop),

byrow = TRUE

)

head(matlp)## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] -0.62 0.62 2.2 Inf

## [2,] -0.62 0.62 2.2 Inf

## [3,] -0.62 0.62 2.2 Inf

## [4,] -0.62 0.62 2.2 Inf

## [5,] -0.62 0.62 2.2 Inf

## [6,] -0.62 0.62 2.2 Inf# set individual thresholds based on covariates,

# which is an additive shift from the reference group

# based on z

matlpInd <- matlp - dt[, z]

head(matlpInd)## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] -1.52 -0.28 1.3 Inf

## [2,] -1.58 -0.34 1.2 Inf

## [3,] -0.95 0.29 1.9 Inf

## [4,] -1.53 -0.29 1.3 Inf

## [5,] -1.49 -0.25 1.3 Inf

## [6,] -1.13 0.11 1.7 Inf# convert log odds to cumulative probabability

matcump <- 1 / (1 + exp(-matlpInd))

matcump <- cbind(0, matcump)

head(matcump)## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] 0 0.18 0.43 0.78 1

## [2,] 0 0.17 0.42 0.78 1

## [3,] 0 0.28 0.57 0.87 1

## [4,] 0 0.18 0.43 0.78 1

## [5,] 0 0.18 0.44 0.79 1

## [6,] 0 0.24 0.53 0.84 1# convert cumulative probs to category probs:

# originally, I used a loop to do this, but

# thought it would be better to vectorize.

# see 2nd addendum for time comparison - not

# much difference

p <- t(t(matcump)[-1,] - t(matcump)[-5,])

# show some indvidual level probabilities

head(p)## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 0.18 0.25 0.36 0.22

## [2,] 0.17 0.24 0.36 0.22

## [3,] 0.28 0.29 0.29 0.13

## [4,] 0.18 0.25 0.36 0.22

## [5,] 0.18 0.25 0.35 0.21

## [6,] 0.24 0.28 0.32 0.16apply(head(p), 1, sum)## [1] 1 1 1 1 1 1# generate indvidual level category outcomes based on p

cat <- simstudy:::matMultinom(p)

catF <- ordered(cat)

dt[, cat := catF]When we fit the mixed effects model, it is not surprising that we recover the parameters used to generate the data, which were based on the model. The fixed effects were specified as “0.8 * grp + 0.3 * male - 0.2 * status”, the variance of the random group effect was 0.10, and the latent thresholds based on the category probabilities were {-0.62, 0.62, 2.20}:

fmm <- clmm(cat ~ grp + male + status + (1|idS), data=dt)

summary(fmm)## Cumulative Link Mixed Model fitted with the Laplace approximation

##

## formula: cat ~ grp + male + status + (1 | idS)

## data: dt

##

## link threshold nobs logLik AIC niter max.grad cond.H

## logit flexible 24990 -33096.42 66206.85 705(2118) 2.37e-02 1.3e+02

##

## Random effects:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

## idS (Intercept) 0.109 0.331

## Number of groups: idS 100

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## grp 0.8117 0.0702 11.6 <2e-16 ***

## male 0.3163 0.0232 13.7 <2e-16 ***

## status -0.1959 0.0116 -16.9 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Threshold coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value

## 1|2 -0.6478 0.0511 -12.7

## 2|3 0.6135 0.0511 12.0

## 3|4 2.1789 0.0529 41.2Addendum 2 - vector vs loop

In case any one is obsessed with vectorization in R, here is a comparison of two different functions that convert cumulative probabilities into probabilities. One method uses a loop, the other uses matrix operations. In this case, it actually appears that my non-loop approach is slower - maybe there is a faster way? Maybe not, since the loop is actually quite short - determined by the number of possible responses in the categorical measure…

library(microbenchmark)

loopdif <- function(mat) {

ncols <- ncol(mat)

p <- matrix(0, nrow = nrow(mat), ncol = ( ncols - 1 ))

for (i in 1 : ( ncol(mat) - 1 )) {

p[,i] <- mat[, i+1] - mat[, i]

}

return(p)

}

vecdif <- function(mat) {

ncols <- ncol(mat)

p <- t(t(mat)[-1,] - t(mat)[-ncols,])

return(p)

}

head(loopdif(matcump))## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 0.18 0.25 0.36 0.22

## [2,] 0.17 0.24 0.36 0.22

## [3,] 0.28 0.29 0.29 0.13

## [4,] 0.18 0.25 0.36 0.22

## [5,] 0.18 0.25 0.35 0.21

## [6,] 0.24 0.28 0.32 0.16head(vecdif(matcump))## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 0.18 0.25 0.36 0.22

## [2,] 0.17 0.24 0.36 0.22

## [3,] 0.28 0.29 0.29 0.13

## [4,] 0.18 0.25 0.36 0.22

## [5,] 0.18 0.25 0.35 0.21

## [6,] 0.24 0.28 0.32 0.16microbenchmark(loopdif(matcump), vecdif(matcump),

times = 1000L, unit = "ms")## Unit: milliseconds

## expr min lq mean median uq max neval

## loopdif(matcump) 0.96 1.4 1.9 1.7 1.9 112 1000

## vecdif(matcump) 0.92 1.7 3.1 2.3 2.7 115 1000