Analysis is important, but study design is paramount. I am involved with the Diabetes Research, Education, and Action for Minorities (DREAM) Initiative, which is, among other things, estimating the effect of a group-based therapy program on weight loss for patients who have been identified as pre-diabetic (which means they have elevated HbA1c levels). The original plan was to randomize patients at a clinic to treatment or control, and then follow up with those assigned to the treatment group to see if they wanted to participate. The primary outcome is going to be measured using medical records, so those randomized to control (which basically means nothing special happens to them) will not need to interact with the researchers in any way.

The concern with this design is that only those patients randomized to the intervention arm of the study have an opportunity to make a choice about participating. In fact, in a pilot study, it was quite difficult to recruit some patients, because the group therapy sessions were frequently provided during working hours. So, even if the groups are balanced after randomization with respect to important (and unimportant characteristics) like age, gender, weight, baseline A1c levels, etc., the patients who actually receive the group therapy might look quite different from the patients who receive treatment as usual. The decision to actually participate in group therapy is not randomized, so it is possible (maybe even likely) that the group getting the therapy is older and more at risk for diabetes (which might make them more motivated to get involved) than those in the control group.

One solution is to analyze the outcomes for everyone randomized, regardless of whether or not they participate (as an intent-to-treat analysis). This estimate would answer the question about how effective the therapy would be in a setting where the intervention is made available; this intent-to-treat estimate does not say how effective the therapy is for the patients who actually choose to receive it. To answer this second question, some sort of as-treated analysis could be used. One analytic solution would be to use an instrumental variable approach. (I wrote about non-compliance in a series of posts starting here.)

However, we decided to address the issue of differential non-participation in the actual design of the study. In particular, we have modified the randomization process with the aim of eliminating any potential bias. The post-hoc IV analysis is essentially a post-hoc matched analysis (it estimates the treatment effect only for the compliers - those randomized to treatment who actually participate in treatment); we hope to construct the groups prospectively to arrive at the same estimate.

The matching strategy

The idea is quite simple. We will generate a list of patients based on a recent pre-diabetes diagnosis. From that list, we will draw a single individual and then find a match from the remaining individuals. The match will be based on factors that the researchers think might be related to the outcome, such as age, gender, and one or two other relevant baseline measures. (If the number of matching characteristics grows too large, matching may turn out to be difficult.) If no match is found, the first individual is removed from the study. If a match is found, the first individual is assigned to the therapy group, and the second to the control group. Now we repeat the process, drawing another individual from the list (which excludes the first pair and any patients who have been unmatched), and finding a match. The process is repeated until everyone on the list has been matched or placed on the unmatched list.

After the pairs have been created, the research study coordinators reach out to the individuals who have been randomized to the therapy group in an effort to recruit participants. If a patient declines, she and her matched pair are removed from the study (i.e. their outcomes will not be included in the final analysis). The researchers will work their way down the list until enough people have been found to participate.

We try to eliminate the bias due to differential dropout by removing the matched patient every time a patient randomized to therapy declines to participate. We are making a key assumption here: the matched patient of someone who agrees to participate would have also agreed to participate. We are also assuming that the matching criteria are sufficient to predict participation. While we will not completely remove bias, it may be the best we can do given the baseline information we have about the patients. It would be ideal if we could ask both members of the pair if they would be willing to participate, and remove them both if one declines. However, in this particular study, this is not feasible.

The matching algorithm

I implemented this algorithm on a sample data set that includes gender, age, and BMI, the three characteristics we want to match. The data is read directly into an R data.table dsamp. I’ve printed the first six rows:

dsamp <- fread("DataMatchBias/eligList.csv")

setkey(dsamp, ID)

dsamp[1:6]## ID female age BMI

## 1: 1 1 24 27.14

## 2: 2 0 29 31.98

## 3: 3 0 47 25.28

## 4: 4 0 40 24.27

## 5: 5 1 29 30.61

## 6: 6 1 38 25.69The loop below selects a single record from dsamp and searches for a match. If a match is found, the selected record is added to drand (randomized to therapy) and the match is added to dcntl. If no match is found, the single record is added to dused, and nothing is added to drand or dcntl. Anytime a record is added to any of the three data tables, it is removed from dsamp. This process continues until dsamp has one or no records remaining.

The actual matching is done by a call to function Match from the Matching package. This function is typically used to match a group of exposed to unexposed (or treated to untreated) individuals, often using a propensity score. In this case, we are matching simultaneously on the three columns in dsamp. Ideally, we would want to have exact matches, but this is unrealistic for continuous measures. So, for age and BMI, we set the matching range to be 0.5 standard deviations. (We do match exactly on gender.)

library(Matching)

set.seed(3532)

dsamp[, rx := 0]

dused <- NULL

drand <- NULL

dcntl <- NULL

while (nrow(dsamp) > 1) {

selectRow <- sample(1:nrow(dsamp), 1)

dsamp[selectRow, rx := 1]

myTr <- dsamp[, rx]

myX <- as.matrix(dsamp[, .(female, age, BMI)])

match.dt <- Match(Tr = myTr, X = myX,

caliper = c(0, 0.50, .50), ties = FALSE)

if (length(match.dt) == 1) { # no match

dused <- rbind(dused, dsamp[selectRow])

dsamp <- dsamp[-selectRow, ]

} else { # match

trt <- match.dt$index.treated

ctl <- match.dt$index.control

drand <- rbind(drand, dsamp[trt])

dcntl <- rbind(dcntl, dsamp[ctl])

dsamp <- dsamp[-c(trt, ctl)]

}

}Matching results

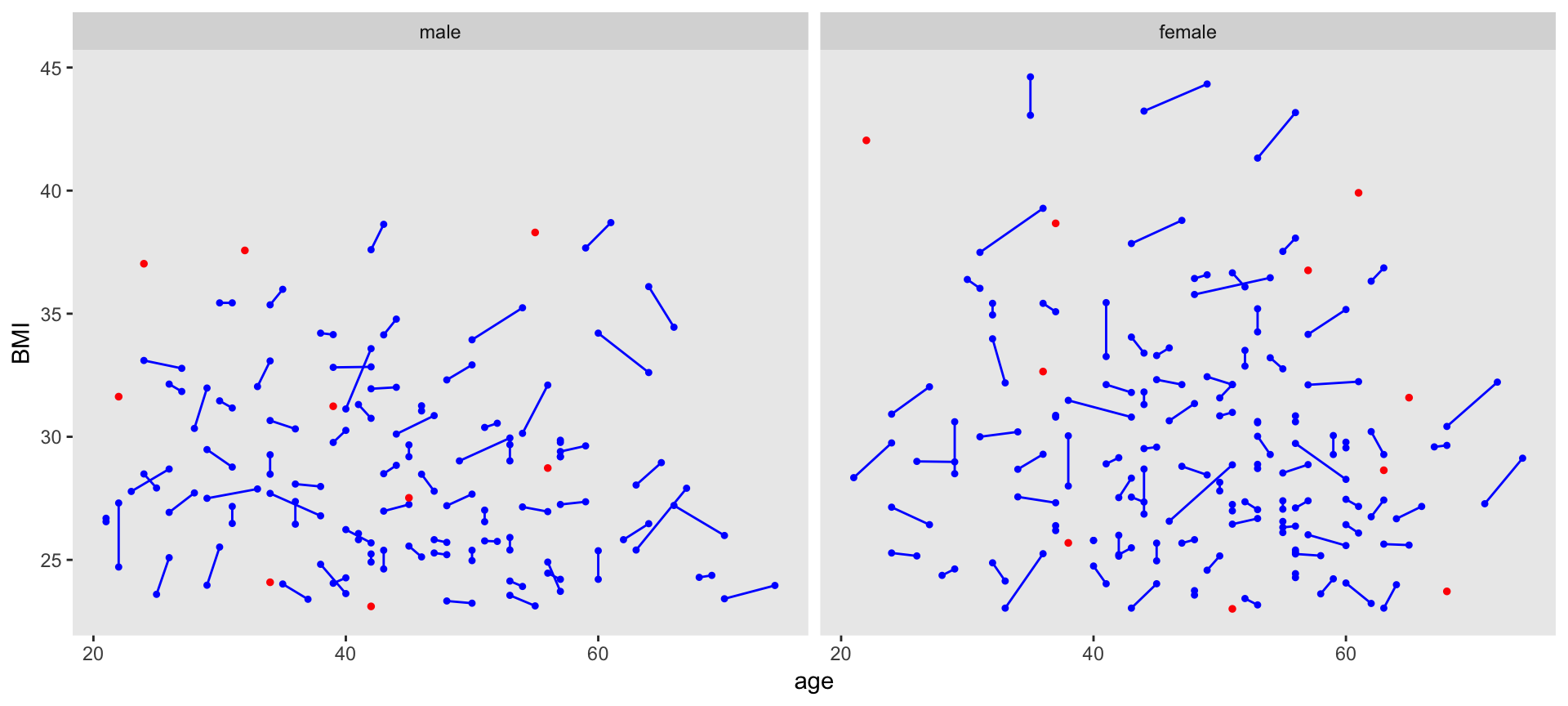

Here is a plot of all the pairs that were generated (connected by the blue segment), and includes the individuals without a match (red circles). We could get shorter line segments if we reduced the caliper values, but we would certainly increase the number of unmatched patients.

The distributions of the matching variables (or least the means and standard deviations) appear quite close, as we can see by looking at the males and females separately.

Males

## rx N mu.age sd.age mu.bmi sd.bmi

## 1: 0 77 44.8 12.4 28.6 3.65

## 2: 1 77 44.6 12.4 28.6 3.71Females

## rx N mu.age sd.age mu.bmi sd.bmi

## 1: 0 94 47.8 11.1 29.7 4.63

## 2: 1 94 47.8 11.3 29.7 4.55Incorporating the design into the analysis plan

The study - which is formally named Integrated Community-Clinical Linkage Model to Promote Weight Loss among South Asians with Pre-Diabetes - is still in its early stages, so no outcomes have been collected. But when it comes time to analyzing the results, the models used to estimate the effect of the intervention will have to take into consideration two important design factors: (1) the fact that the individuals in the treatment and control groups are not independent, because they were assigned to their respective groups in pairs, and (2) the fact that the individuals in the treatment groups will not be independent of each other, since the intervention is group-based, so this a partially cluster randomized trial. In a future post, I will explore this model in a bit more detail.

This study is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases R01DK11048. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding organizations.