I’m part of a team that recently submitted the results of a randomized clinical trial for publication in a journal. The overall findings of the study were inconclusive, and we certainly didn’t try to hide that fact in our paper. Of course, the story was a bit more complicated, as the RCT was conducted during various phases of the COVID-19 pandemic; the context in which the therapeutic treatment was provided changed over time. In particular, other new treatments became standard of care along the way, resulting in apparent heterogeneous treatment effects for the therapy we were studying. It appears as if the treatment we were studying might have been effective only in one period when alternative treatments were not available. While we planned to evaluate the treatment effect over time, it was not our primary planned analysis, and the journal objected to the inclusion of the these secondary analyses.

Which got me thinking, of course, about subgroup analyses. In the context of a null hypothesis significance testing framework, it is well known that conducting numerous post hoc analyses carries the risk of dramatically inflating the probability of a Type 1 error - concluding there is some sort of effect when in fact there is none. So, if there is no overall effect, and you decide to look at a subgroup of the sample (say patients over 50), you may find that the treatment has an effect in that group. But, if you failed to adjust for multiple tests, than that conclusion may not be warranted. And if that second subgroup analysis was not pre-specified or planned ahead of time, that conclusion may be even more dubious.

If we use a Bayesian approach, we might be able to avoid this problem, and there might be no need to adjust for multiple tests. I have started to explore this a bit using simulated data under different data generation processes and prior distribution assumptions. It might all be a bit too much for a single post, so I am planning on spreading it out a bit.

The data

To get this going, here are the libraries used in this post:

library(simstudy)

library(data.table)

library(ggplot2)

library(cmdstanr)

library(posterior)In this simulated data set of 150 individuals, there are three binary covariates and a treatment indicator . When we randomize the individuals to arms, we should have pretty good balance across treatment arms, so a comparison of the two treatment arms without adjusting for the covariates should provide a good estimate of the overall treatment effect. However, we might still be interested in looking at specific subgroups defined by , , and , say patients for whom or those where . (We could also look at subgroups defined by combinations of these covariates.)

In the data generation process, the treatment effect will be a parameter that will be determined by the levels of the three covariates. In this case, for patients , there will be no treatment effect. However, for patients with only (i.e., and ), there will be a small treatment effect of , and there will be a slightly larger effect of for patients with , and for patients with , there will be a treatment effect of . For patients with (alone) there is no treatment effect.

d <- defData(varname = "a", formula = 0.6, dist="binary")

d <- defData(d, varname = "b", formula = 0.3, dist="binary")

d <- defData(d, varname = "c", formula = 0.4, dist="binary")

d <- defData(d, varname = "theta", formula = "0 + 2*a + 4*c - 1*a*c", dist = "nonrandom")

drx <- defDataAdd(varname = "y", formula = "0 + theta*rx", variance = 16, dist = "normal")In the data generation process, I am assigning eight group identifiers based on the covariates that will be relevant for the Bayes model (described further below).

setgrp <- function(a, b, c) {

if (a==0 & b==0 & c==0) return(1)

if (a==1 & b==0 & c==0) return(2)

if (a==0 & b==1 & c==0) return(3)

if (a==0 & b==0 & c==1) return(4)

if (a==1 & b==1 & c==0) return(5)

if (a==1 & b==0 & c==1) return(6)

if (a==0 & b==1 & c==1) return(7)

if (a==1 & b==1 & c==1) return(8)

}To generate the data:

set.seed(3871598)

dd <- genData(150, d)

dd <- trtAssign(dd, grpName = "rx")

dd <- addColumns(drx, dd)

dd[, grp:= setgrp(a, b, c), keyby = id]

dd## id a b c theta rx y grp

## 1: 1 1 0 1 5 0 0.28 6

## 2: 2 1 1 0 2 0 3.14 5

## 3: 3 0 0 0 0 0 0.73 1

## 4: 4 1 1 0 2 1 0.78 5

## 5: 5 1 1 1 5 0 -5.94 8

## ---

## 146: 146 1 1 0 2 1 4.68 5

## 147: 147 0 0 1 4 0 3.10 4

## 148: 148 1 0 0 2 0 5.88 2

## 149: 149 1 1 1 5 1 4.22 8

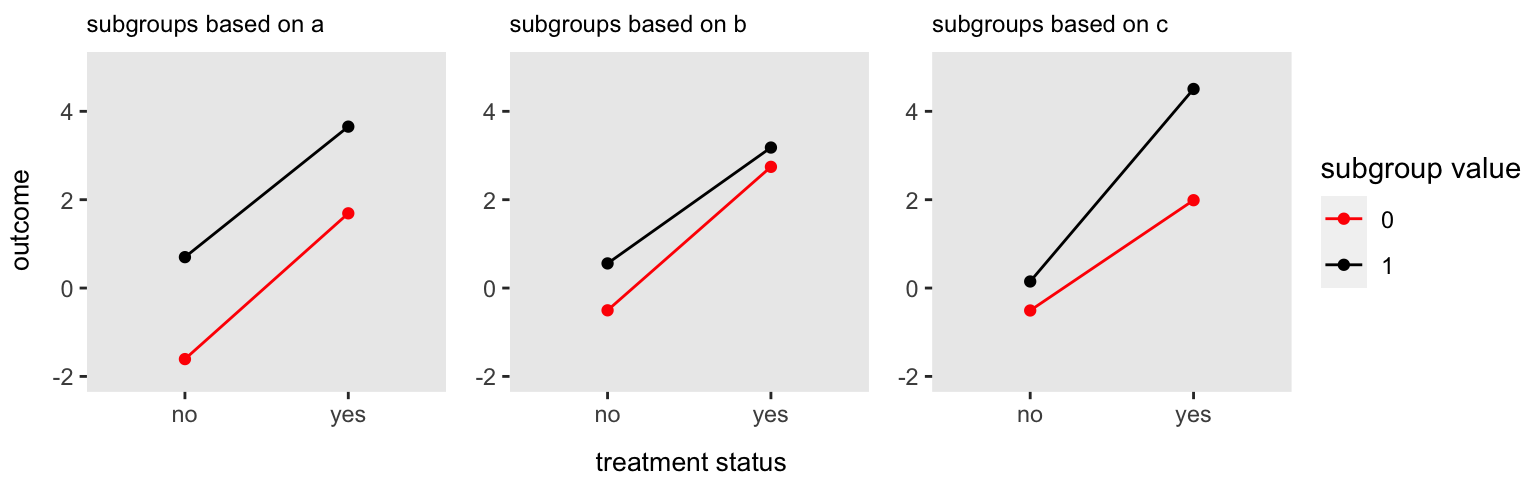

## 150: 150 0 1 1 4 1 4.76 7Here is a plot of the average outcome for each of the subgroups with and without treatment. The treatment effect for a particular subgroup is the difference of the values for each segment. Now, it appears that there is a treatment effect for the two subgroups and , yet was not supposed to have any impact on the overall effect size, which is . Just in case this is at all confusing, this is due to the fact that these patients have characteristics and , which do influence the effect size. Indeed, if you compare the subgroups and , it appears that the effect size could be the same, which is consistent with the fact that has no impact on effect size. This is definitely not the case when comparing and . I point this out, because when I report the estimated effect sizes from the models, I will be reporting the subgroup-specific effects shown here, rather than parameter estimates of .

Subgroup analysis using simple linear regression

Before jumping into the Bayes models, I am fitting seven simple linear regression models to estimate seven treatment effects, one for each of the six subgroups defined by the covariates , , and , plus an overall estimate.

df <- data.frame(dd)

est_lm <- function(dx) {

fit <- lm(y ~ rx, data = dx)

c(coef(fit)["rx"], confint(fit)[2,])

}

est_cis <- function(sub_grp) {

mean_pred <- lapply(split(df[,c(sub_grp, "y", "rx")], df[, c(sub_grp)]), est_lm)

do.call(rbind, mean_pred)

}

ci_subgroups <- do.call(rbind, lapply(c("a","b","c"), est_cis))

ci_overall <- est_lm(dd)

cis <- data.table(

subgroup = c("a = 0", "a = 1", "b = 0", "b = 1", "c = 0", "c = 1", "overall"),

model = 3,

rbind(ci_subgroups, ci_overall)

)

setnames(cis, c("rx","2.5 %", "97.5 %"), c("p.50","p.025", "p.975"))Inspecting the point estimates (denoted as p.50 for the treatment effect for each subgroup (and the overall group), we see that they match pretty closely with the effect sizes depicted in the figure of the means by subgroup above. I’ll compare these estimates to the Bayes estimates in a bit.

cis## subgroup model p.50 p.025 p.975

## 1: a = 0 3 3.3 1.30 5.3

## 2: a = 1 3 3.0 1.31 4.6

## 3: b = 0 3 3.2 1.57 4.9

## 4: b = 1 3 2.6 0.61 4.6

## 5: c = 0 3 2.5 0.90 4.1

## 6: c = 1 3 4.4 2.19 6.5

## 7: overall 3 3.1 1.79 4.4Two possible Bayesian models

I am including two Bayesian models here, one that I am calling a pooled model and the other an unpooled model (though the second is not absolutely unpooled, just relatively unpooled). In both cases, the outcome model is described as

where is the outcome measure for individual who has covariate/subgroup pattern . (These subgroup patterns were defined above in R code. For example group 1 is all cases where and group 5 is .) is a treatment indicator, . is the intercept for covariate pattern (representing the mean outcome for all patients with pattern randomized to control). represents the treatment effect for patients with pattern . is the within treatment arm/covariate pattern standard deviation, and is assumed to be constant across arms and patterns.

The treatment effect parameter can be further parameterized as function of a set of (This parameterization was inspired by this paper by Jones et al.) The treatment effect is a deterministic function of the covariates , , and as well as their interactions:

So far, the parameterization for the pooled and unpooled models are the same. Now we see how they diverge:

Pooled model

The idea behind the pooled model is that the main effects of , , (, , and , respectively) are drawn from the same distribution centered around with a standard deviation , both of which will be estimated from the data. The estimated effect of one covariate will, to some extent, inform the estimated effect of the others. Of course, as the number of observations increases, the strength of pooling will be reduced. The three 2-level interaction effects (, and ) are independent of the main effects, but they also share a common distribution to be estimated from the data. (In this case we have only a single three-way interaction term , but if we had 4 covariates rather than 3, we would have 4 three-way interaction terms, which could all share the same prior distribution. At some point, it might be reasonable to exclude higher order interactions, such as four- or five-way interactions.)

With the exception of and , the prior distributions for the model parameters are quite conservative/pessimistic, centered pretty closely around 0. (It would certainly be wise to explore how these prior assumptions impact the findings, but since this is just an illustrative example, I won’t dwell too much on these particular assumptions).

Unpooled model

In the unpooled model, the ’s (and ’s) are not jointly parameterized with a common mean, and the prior distributions are more diffuse. The only variance estimation is for :

Model estimation

I’m using cmdstanr to estimate the models in Stan. (The Stan code is available if any anyone is interested, or you can try to write it yourself.) For each model, I am sampling in 4 chains of length 2500 following 500 warm-up steps. I’ll skip the required diagnostics here (e.g. trace plots) for brevity, but I did check everything, and things looked OK.

model_pool <- cmdstan_model("code/pooled_subgroup.stan")

model_unpool <- cmdstan_model("code/unpooled_subgroup.stan")fit_pool <- model_pool$sample(

data = list(N = dd[,.N], rx = dd[,rx], sub_grp = dd[,grp], y=dd[,y]),

refresh = 0,

chains = 4L,

parallel_chains = 4L,

iter_warmup = 500,

iter_sampling = 2500,

adapt_delta = 0.99,

max_treedepth = 20,

seed = 898171

)## Running MCMC with 4 parallel chains...

##

## Chain 1 finished in 1.4 seconds.

## Chain 2 finished in 1.4 seconds.

## Chain 3 finished in 1.5 seconds.

## Chain 4 finished in 1.6 seconds.

##

## All 4 chains finished successfully.

## Mean chain execution time: 1.5 seconds.

## Total execution time: 1.8 seconds.fit_unpool <- model_unpool$sample(

data = list(N = dd[,.N], rx = dd[,rx], sub_grp = dd[,grp], y=dd[,y], prior_sigma=10),

refresh = 0,

chains = 4L,

parallel_chains = 4L,

iter_warmup = 500,

iter_sampling = 2500,

adapt_delta = 0.99,

max_treedepth = 20,

seed = 18717

)## Running MCMC with 4 parallel chains...

##

## Chain 3 finished in 1.4 seconds.

## Chain 2 finished in 1.5 seconds.

## Chain 4 finished in 1.7 seconds.

## Chain 1 finished in 2.1 seconds.

##

## All 4 chains finished successfully.

## Mean chain execution time: 1.7 seconds.

## Total execution time: 2.2 seconds.Extracting posterior probabilities

In this case, I am actually not directly interested in the effect parameters , but actually in the estimated treatment effects for the six subgroups defined by , , , , , and . (These groups are not distinct from one another, as each individual has measures for each of , , and .) I will step through the process of how I get these estimates, and then will plot a summary of the estimates.

First, I extract the key parameter estimates into an rvars data structure (I discussed this data structure recently in a couple of posts - here and here). Although the object r below looks like a list of 3 items with just a handful of values, there is actually an entire data set supporting each value that contains 10,000 samples from the posterior distribution. What we are seeing are the mean and standard deviation of those distributions.

r <- as_draws_rvars(fit_pool$draws(variables = c("alpha","theta","sigma")))

r## # A draws_rvars: 2500 iterations, 4 chains, and 3 variables

## $alpha: rvar<2500,4>[8] mean ± sd:

## [1] -2.42 ± 0.89 0.49 ± 0.79 -1.61 ± 1.46 -0.88 ± 1.09 0.93 ± 1.30

## [6] 1.06 ± 0.89 2.64 ± 1.59 -0.18 ± 1.19

##

## $theta: rvar<2500,4>[8] mean ± sd:

## [1] 2.1 ± 1.03 2.8 ± 0.89 2.7 ± 1.10 3.6 ± 1.11 2.6 ± 1.31 4.2 ± 1.17

## [7] 4.0 ± 1.31 3.6 ± 1.72

##

## $sigma: rvar<2500,4>[1] mean ± sd:

## [1] 3.8 ± 0.23A cool feature of the rvars data structure (which is part of the package posterior) is that they can be stored in a data.frame, and easily manipulated. Here I am matching the to each individual depending on their covariate pattern . The plan is to generate simulated data for each individual based on the estimated means and standard deviations.

df <- as.data.frame(dd)

df$theta_hat <- r$theta[dd$grp]

df$alpha_hat <- r$alpha[dd$grp]

df$mu_hat <- with(df, alpha_hat + rx* theta_hat)Here are the first ten rows (out of the 150 individual records):

head(df, 10)## id a b c theta rx y grp theta_hat alpha_hat mu_hat

## 1 1 1 0 1 5 0 0.28 6 4.2 ± 1.17 1.06 ± 0.89 1.06 ± 0.89

## 2 2 1 1 0 2 0 3.14 5 2.6 ± 1.31 0.93 ± 1.30 0.93 ± 1.30

## 3 3 0 0 0 0 0 0.73 1 2.1 ± 1.03 -2.42 ± 0.89 -2.42 ± 0.89

## 4 4 1 1 0 2 1 0.78 5 2.6 ± 1.31 0.93 ± 1.30 3.52 ± 0.96

## 5 5 1 1 1 5 0 -5.94 8 3.6 ± 1.72 -0.18 ± 1.19 -0.18 ± 1.19

## 6 6 1 1 1 5 0 -1.45 8 3.6 ± 1.72 -0.18 ± 1.19 -0.18 ± 1.19

## 7 7 1 1 0 2 0 5.47 5 2.6 ± 1.31 0.93 ± 1.30 0.93 ± 1.30

## 8 8 1 1 0 2 1 -2.33 5 2.6 ± 1.31 0.93 ± 1.30 3.52 ± 0.96

## 9 9 0 0 1 4 1 0.84 4 3.6 ± 1.11 -0.88 ± 1.09 2.69 ± 1.06

## 10 10 1 0 0 2 1 7.05 2 2.8 ± 0.89 0.49 ± 0.79 3.26 ± 0.78We can add a column of predicted “values” to the data frame.

df$pred <- rvar_rng(rnorm, nrow(df), df$mu_hat, r$sigma)

head(df[,c("id", "grp", "mu_hat", "pred")], 10)## id grp mu_hat pred

## 1 1 6 1.06 ± 0.89 1.01 ± 3.9

## 2 2 5 0.93 ± 1.30 0.95 ± 4.0

## 3 3 1 -2.42 ± 0.89 -2.41 ± 3.9

## 4 4 5 3.52 ± 0.96 3.53 ± 3.9

## 5 5 8 -0.18 ± 1.19 -0.19 ± 4.0

## 6 6 8 -0.18 ± 1.19 -0.18 ± 4.0

## 7 7 5 0.93 ± 1.30 0.90 ± 4.1

## 8 8 5 3.52 ± 0.96 3.49 ± 3.9

## 9 9 4 2.69 ± 1.06 2.67 ± 3.9

## 10 10 2 3.26 ± 0.78 3.30 ± 3.9But note that we don’t just have a single value for each of the 150 individuals, but 10,000 samples for each of the 150 individuals (for a total 1.5 million predicted values.) Here is a little bit of evidence that this is the case, as you can see that this is an rvar of dimension , or predicted values:

df[9, "pred"]## rvar<2500,4>[1] mean ± sd:

## [1] 2.7 ± 3.9Finally, we are ready to get estimates of the within-subgroup effect sizes. I’ve written a little function to help out here. For each covariate , , and , the function splits the data set into four subsets. So, for covariate we have , , , and . For each of those subsets, we get a distribution of mean predicted values by averaging across the distribution of individual predicted values. So, the variable effects contains the distribution of effects for the six subgroups (, , , , , and ):

est_effects <- function(sub_grp) {

mean_pred <- lapply(split(df[,c(sub_grp, "rx","pred")], df[, c(sub_grp, "rx")]),

function(x) rvar_mean(x$pred)

)

c(mean_pred[["0.1"]] - mean_pred[["0.0"]], mean_pred[["1.1"]] - mean_pred[["1.0"]])

}

effects <- do.call(c, lapply(c("a","b","c"), est_effects))

effects## rvar<2500,4>[6] mean ± sd:

## [1] 2.5 ± 1.3 3.2 ± 1.1 2.8 ± 1.0 3.1 ± 1.5 2.7 ± 1.1 3.5 ± 1.3We can also get the distribution of the overall (marginal) treatment effect by sub-setting by only. The last step is to create a summary table for the pooled model. Remember, the effects table is really a table of distributions, and we can extract summary statistics from those distributions for reporting or plotting. Here, we are extracting the , , and quantiles to show the median and a interval.

mean_pred <- lapply(split(df[,c("rx","pred")], df[, "rx"]), function(x) rvar_mean(x$pred))

overall <- mean_pred[["1"]] - mean_pred[["0"]]

effects <- c(effects, overall)

sumstats_pooled <- data.table(

subgroup = c("a = 0", "a = 1", "b = 0", "b = 1", "c = 0", "c = 1", "overall"),

model = 1,

p.025 = quantile(effects, 0.025),

p.50 = quantile(effects, 0.50),

p.975 = quantile(effects, 0.975)

)Comparing model estimates

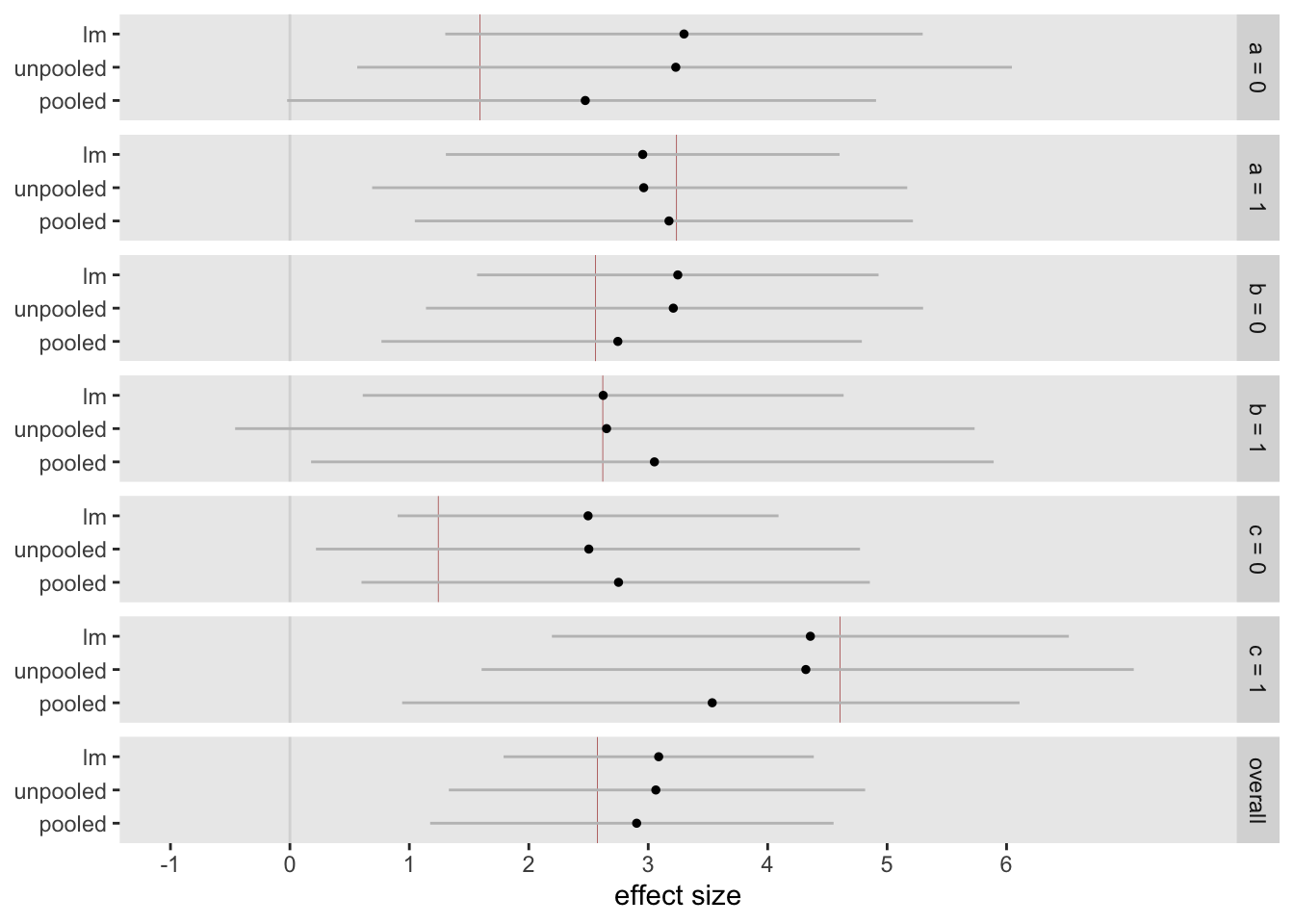

Now to take a look at the distribution of effect sizes based on the different models. (I didn’t show it, but I also created a table called sumstats_unpooled using the same process I just walked you through.) Below is a plot of the effect estimates for each of the subgroups as well as the overall (marginal) effect estimates. The lm plot shows the point estimate with a confidence interval. The other two plots show the medians of the posterior distributions for the subgroup effects along with intervals.

Two important things to see in the plot, which will be very important when I write next time about “Type 1” errors, are the relative length of the intervals and the apparent shrinkage of some of the estimates. In all the cases, the length of the interval for the standard linear regression model is smaller than the two Bayesian models, reflecting less uncertainty. The pooled model also appears to have slightly less uncertainty compared to the unpooled model.

The second point is that the point estimates for the linear regression model and the median estimates for the unpooled model are quite close, while the pooled medians appear to be pulled away. The direction of the shrinkage is not coherent, because there is a mixture of main effects and interaction effects (the ’s) that are shifting things around. It appears that the effects of the subgroups and are being pulled towards each other, and the same appears to be true for the group defined by and This seems right as we know that the underlying parameters , , and are shrinking towards each other.

If we were using the pooled model to draw conclusions, I would say that it appears that subgroups defined by seem to have heterogeneous treatment effects, though I would probably want to have more data to confirm, as the intervals are still quite wide. If we use the results from the linear regression model, we might want to proceed with caution, because the intervals are likely too narrow, we have not adjusted for multiple testing. We will see this next time when I look at a case where there are no underlying treatment effects in the data generation process.

Reference:

Jones, Hayley E., David I. Ohlssen, Beat Neuenschwander, Amy Racine, and Michael Branson. “Bayesian models for subgroup analysis in clinical trials.” Clinical Trials 8, no. 2 (2011): 129-143.