The odds ratio (OR) – the effect size parameter estimated in logistic regression – is notoriously difficult to interpret. It is a ratio of two quantities (odds, under different conditions) that are themselves ratios of probabilities. I think it is pretty clear that a very large or small OR implies a strong treatment effect, but translating that effect into a clinical context can be challenging, particularly since ORs cannot be mapped to unique probabilities.

One alternative measure of effect is the risk difference, which is certainly much more intuitive. Although a difference is very easy to calculate when measured non-parametrically (you just calculate the proportion for each arm and take the difference), things get a little less obvious when there are covariates that need adjusting. (There is a method developed by Richardson, Robins, & Wang, that allow analysts to model the risk difference, but I won’t get into that here.)

Currently, I’m working on an NIA IMPACT Collaboratory study evaluating an intervention designed to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates for staff and long-term residents in nursing facilities. A collaborator suggested we report the difference in vaccination rates rather than the odds ratio, arguing in favor of the more intuitive measure. From my perspective, the only possible downside in using a risk difference instead of an OR is that risk difference estimates are marginal, whereas odds ratios are conditional. (I’ve written about this distinction before.) The marginal risk difference estimate is a function of the distribution of patient characteristics in the study that influence the outcome, so the reported estimate might not be generalizable to other populations. The odds ratio, on the other hand, is not dependent on the covariates. The ultimate consensus on our research team is that the benefits of improved communication outweigh the potential loss of generalizability.

My goal here is to demonstrate the relative simplicity of estimating the marginal risk difference described in these papers by Kleinman & Norton and Peter Austin. I won’t be using real data from the study that motivated this, but will generate simulated data so that I can illustrate the contrast between marginal and conditional estimates.

Quickly defining the parameters of interest

In the study that motivated this, we had two study arms - an intervention arm which involved extensive outreach and vaccination promotion and the other a control arm where nothing special was done. So, there are two probabilities that we are interested in: and

The risk difference comparing the two groups is simply

the odds for each treatment group is

and the odds ratio comparing the intervention arm to the control arm is

The logistic regression model models the log odds as a linear function of the intervention status and any other covariates that are being adjusted. In the examples below, there is one continuous covariate that ranges from -0.5 to 0.5:

represents the log(OR) conditional on a particular value of :

and

More importantly, we can move between odds and probability relatively easily:

Estimating the marginal probability using model estimates

After fitting the model, we have estimates , , and . We can generate a pair of odds for each individual ( and ) using their observed and the estimated parameters. All we need to do is set and to generate a predicted and , respectively, for each individual. Note we do not pay attention to the actual treatment arm that the individual was randomized to:

or

Likewise,

We get for as

Finally, the marginal risk difference can be estimated as

from all study participants regardless of actual treatment assignment.

Fortunately, in R we don’t need to do any of these calculations as predictions on the probability scale can be extracted from the model fit. Standard errors of this risk difference can be estimated using bootstrap methods.

Simulated data set

Before getting into the simulations, here are the packages needed to run the code shown here:

set.seed(287362)

library(simstudy)

library(data.table)

library(ggplot2)

library(ggthemes)

library(parallel)I am generating a binary outcome that is a function of a continuous covariate that ranges from -0.5 to 0.5. I use the beta distribution to generate which is transformed into . The advantage of this distribution is the flexibility we have in defining the shape. The OR used to generate the outcome is 2.5:

def <- defDataAdd(varname = "x1", formula = "..mu_x", variance = 8, dist = "beta")

def <- defDataAdd(def, varname = "x", formula = "x1 - 0.5", dist = "nonrandom")

def <- defDataAdd(def, varname = "y",

formula = "-2 + log(2.5) * rx + 1.5 * x",

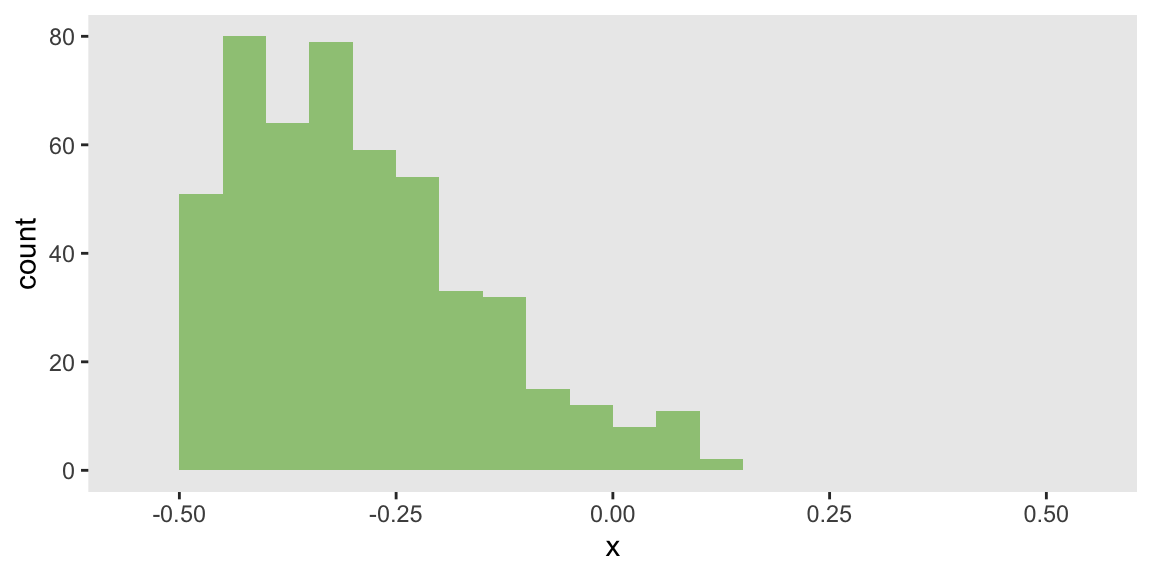

dist = "binary", link="logit")In the first scenario of 500 observations, the distribution of will be right-skewed. This is established by setting the mean of close to 0:

mu_x = 0.2

dd_2 <- genData(500)

dd_2 <- trtAssign(dd_2, grpName = "rx")

dd_2 <- addColumns(def, dd_2)ggplot(data = dd_2, aes(x = x)) +

geom_histogram(fill="#9ec785", binwidth = 0.05, boundary = 0) +

scale_x_continuous(limits = c(-.55, .55), breaks = seq(-.5, .5, by = .25)) +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank())

The first step in estimating the risk difference is to fit a logistic regression model:

glmfit <- glm(y ~ rx + x, data = dd_2, family = "binomial")Next, we need to predict the probability for each individual based on the model fit under each treatment condition. This will give us and :

newdata <- dd_2[, .(rx=1, x)]

p1 <- mean(predict(glmfit, newdata, type = "response"))

newdata <- dd_2[, .(rx=0, x)]

p0 <- mean(predict(glmfit, newdata, type = "response"))

c(p1, p0)## [1] 0.152 0.068A simple calculation gives us the point estimate for the risk difference (and note that the estimated OR is close to 2.5, the value used to generate the data):

risk_diff <- p1 - p0

odds_ratio <- exp(coef(glmfit)["rx"])

c(rd = risk_diff, or = odds_ratio)## rd or.rx

## 0.084 2.456We can use a bootstrap method to estimate a 95% confidence interval for risk difference. This involves sampling ids from each treatment group with replacement, fitting a new logistic regression model, predicting probabilities, and calculating a the risk difference. This is repeated 999 times to get a distribution of risk differences, from which we extract an estimated confidence interval:

bootdif <- function(dd) {

db <- dd[, .(id = sample(id, replace = TRUE)), keyby = rx]

db <- merge(db[, id, rx], dd, by = c("id", "rx"))

glmfit <- glm(y ~ rx + x, data = db, family = "binomial")

newdata <- db[, .(rx=1, x)]

p1 <- mean(predict(glmfit, newdata, type = "response"))

newdata <- db[, .(rx=0, x)]

p0 <- mean(predict(glmfit, newdata, type = "response"))

return(p1 - p0)

}

bootest <- unlist(mclapply(1:999, function(x) bootdif(dd_2), mc.cores = 4))

quantile(bootest, c(0.025, 0.975))## 2.5% 97.5%

## 0.031 0.137Change in distribution changes risk difference

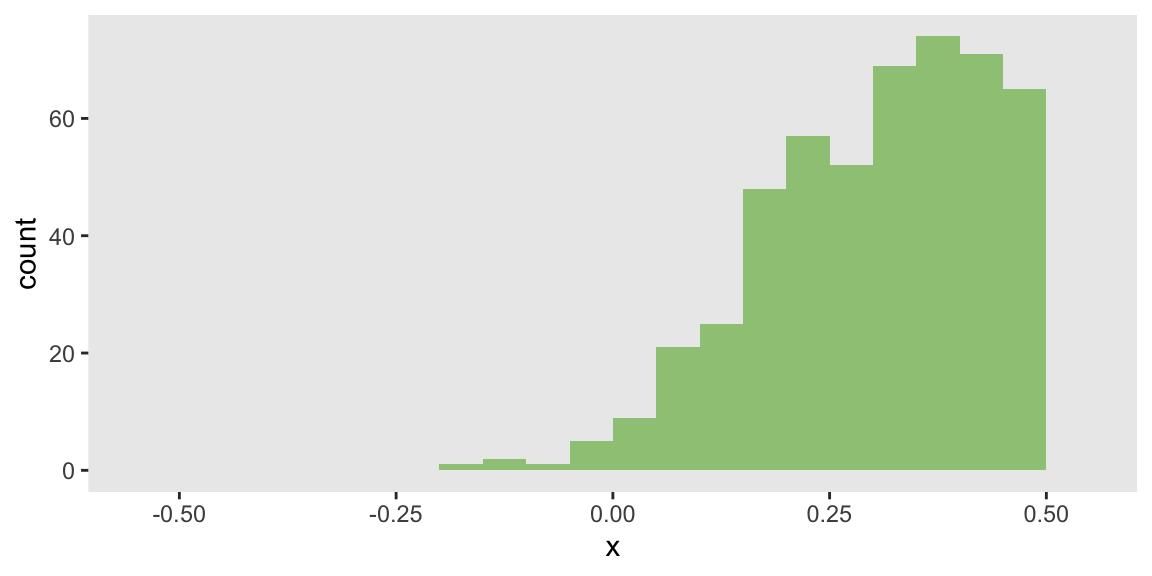

To illustrate how a shift in the distribution of can influence the marginal risk difference without changing the odds ratio, I just need to specify the mean of to be closer to 1. This creates a left-skewed distribution that will increase the risk difference:

mu_x = 0.8

The risk difference appears to increase, but the OR seems to be pretty close to the true value of 2.5:

## rd or.rx

## 0.18 2.59And for completeness, here is the estimated confidence interval:

## 2.5% 97.5%

## 0.10 0.25A more robust comparison

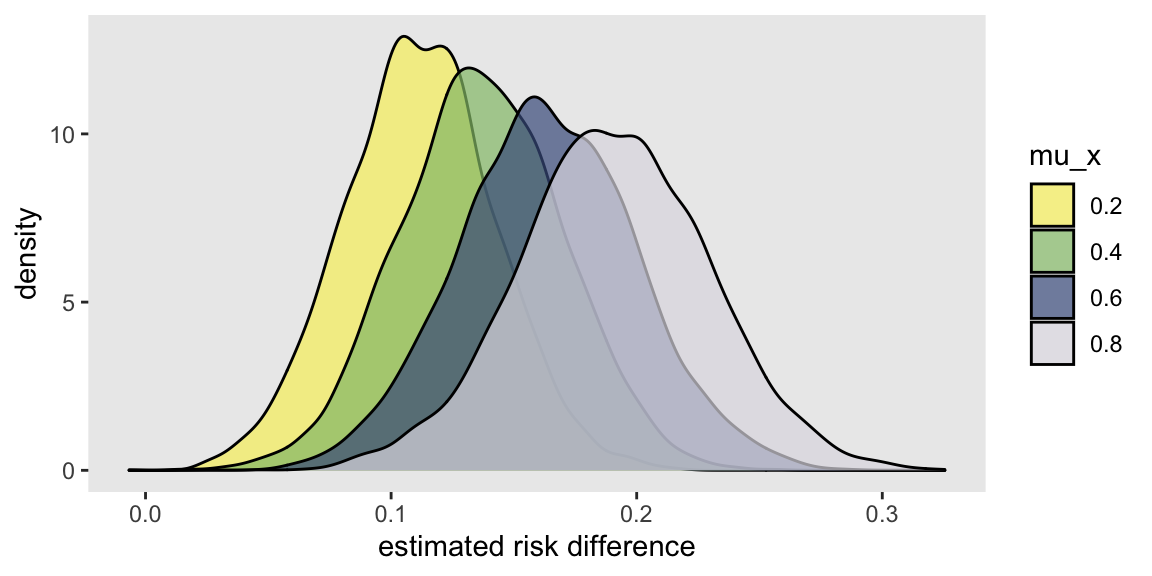

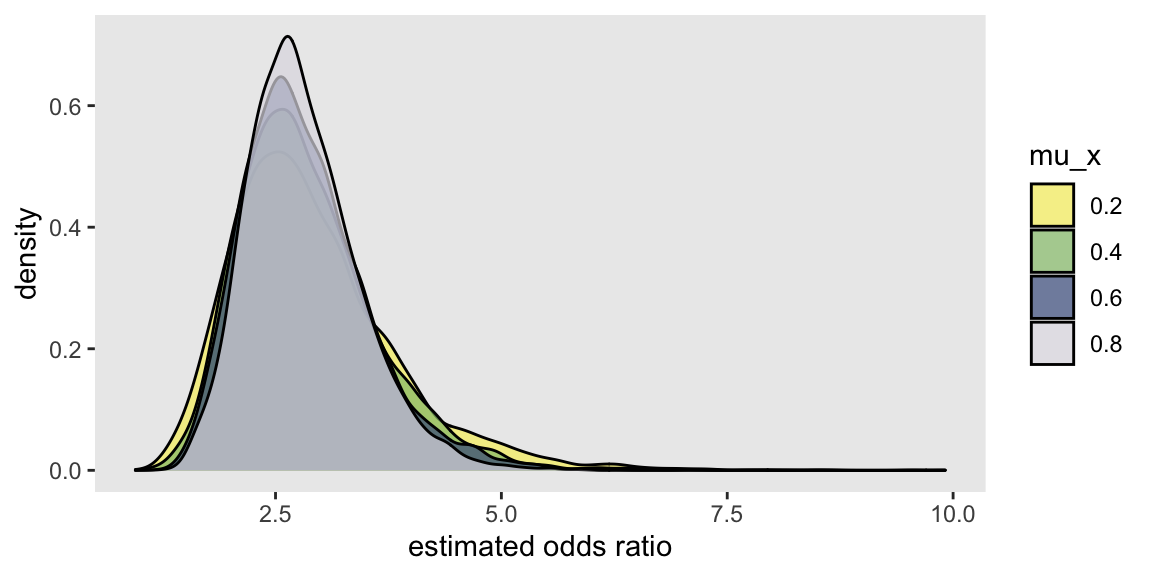

It is hardly fair to evaluate this property using only two data sets. It is certainly possible that the estimated risk differences are inconsistent just by chance. I have written some functions (provided below in the addendum) that facilitate the replication of numerous data sets created under different distribution assumptions to a generate a distribution of estimated risk differences (as well as a distribution of estimated ORs). I have generated 5000 data sets of 500 observations each under four different assumptions of mu_x used in the data generation process defined above: {0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8}.

It is pretty apparent the the risk difference increases as the distribution of shifts from right-skewed to left-skewed:

And it is equally apparent that shifting the distribution has no impact on the OR, which is consistent across different levels of :

References:

Austin, Peter C. “Absolute risk reductions, relative risks, relative risk reductions, and numbers needed to treat can be obtained from a logistic regression model.” Journal of clinical epidemiology 63, no. 1 (2010): 2-6.

Kleinman, Lawrence C., and Edward C. Norton. “What’s the risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression.” Health services research 44, no. 1 (2009): 288-302.

Richardson, Thomas S., James M. Robins, and Linbo Wang. “On modeling and estimation for the relative risk and risk difference.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 112, no. 519 (2017): 1121-1130.

Support:

This work was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54AG063546, which funds the NIA IMbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s Disease and AD-Related Dementias Clinical Trials Collaboratory (NIA IMPACT Collaboratory). The author, a member of the Design and Statistics Core, was the sole writer of this blog post and has no conflicts. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Addendum: replication code

s_define <- function() {

def <- defDataAdd(varname = "x1", formula = "..mu_x", variance = 8, dist = "beta")

def <- defDataAdd(def, varname = "x", formula = "x1 - 0.5", dist = "nonrandom")

def <- defDataAdd(def, varname = "y",

formula = "-2 + 1 * rx + 1.5 * x",

dist = "binary", link="logit")

return(list(def = def)) # list_of_defs is a list of simstudy data definitions

}

s_generate <- function(list_of_defs, argsvec) {

list2env(list_of_defs, envir = environment())

list2env(as.list(argsvec), envir = environment())

dx <- genData(n)

dx <- trtAssign(dx, grpName = "rx")

dx <- addColumns(def, dx)

return(dx) # generated data is a data.table

}

s_model <- function(dx) {

glmfit <- glm(y ~ rx + x, data = dx, family = "binomial")

newdata <- dx[, .(rx=1, x)]

p1 <- mean(predict(glmfit, newdata, type = "response"))

newdata <- dx[, .(rx=0, x)]

p0 <- mean(predict(glmfit, newdata, type = "response"))

risk_diff <- p1 - p0

odds_ratio <- exp(coef(glmfit)["rx"])

model_results <- data.table(risk_diff, odds_ratio)

return(model_results) # model_results is a data.table

}

s_single_rep <- function(list_of_defs, argsvec) {

generated_data <- s_generate(list_of_defs, argsvec)

model_results <- s_model(generated_data)

return(model_results)

}

s_replicate <- function(argsvec, nsim) {

list_of_defs <- s_define()

model_results <- rbindlist(

parallel::mclapply(

X = 1 : nsim,

FUN = function(x) s_single_rep(list_of_defs, argsvec),

mc.cores = 4)

)

model_results <- cbind(t(argsvec), model_results)

return(model_results) # summary_stats is a data.table

}

### Scenarios

scenario_list <- function(...) {

argmat <- expand.grid(...)

return(asplit(argmat, MARGIN = 1))

}

#----

n <- 500

mu_x <- c(0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8)

scenarios <- scenario_list(n = n, mu_x = mu_x)

summary_stats <- rbindlist(lapply(scenarios, function(a) s_replicate(a, nsim = 5000)))

ggplot(data = summary_stats, aes(x = risk_diff, group = mu_x)) +

geom_density(aes(fill = factor(mu_x)), alpha = .7) +

scale_fill_canva(palette = "Simple but bold", name = "mu_x") +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank()) +

xlab("estimated risk difference")

ggplot(data = summary_stats, aes(x = odds_ratio, group = mu_x)) +

geom_density(aes(fill = factor(mu_x)), alpha = .7) +

scale_fill_canva(palette = "Simple but bold", name = "mu_x") +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank()) +

xlab("estimated odds ratio")